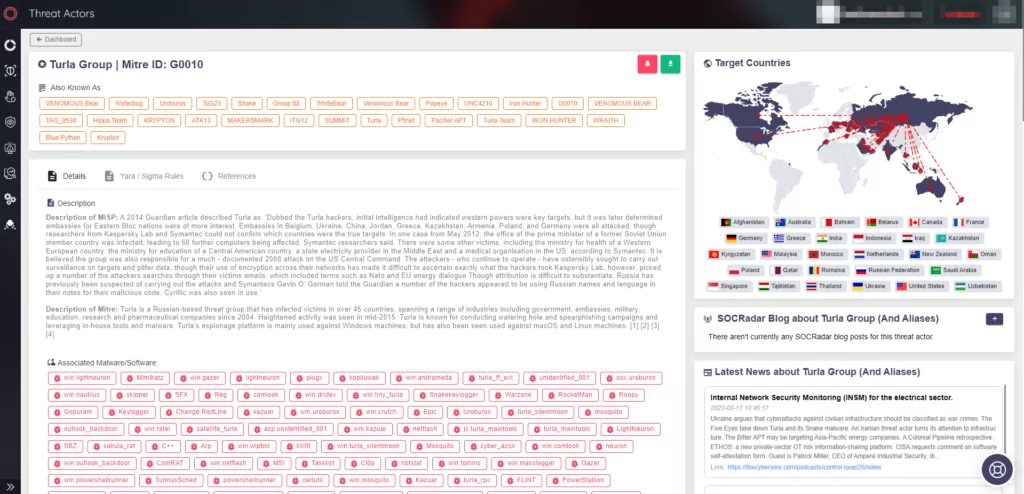

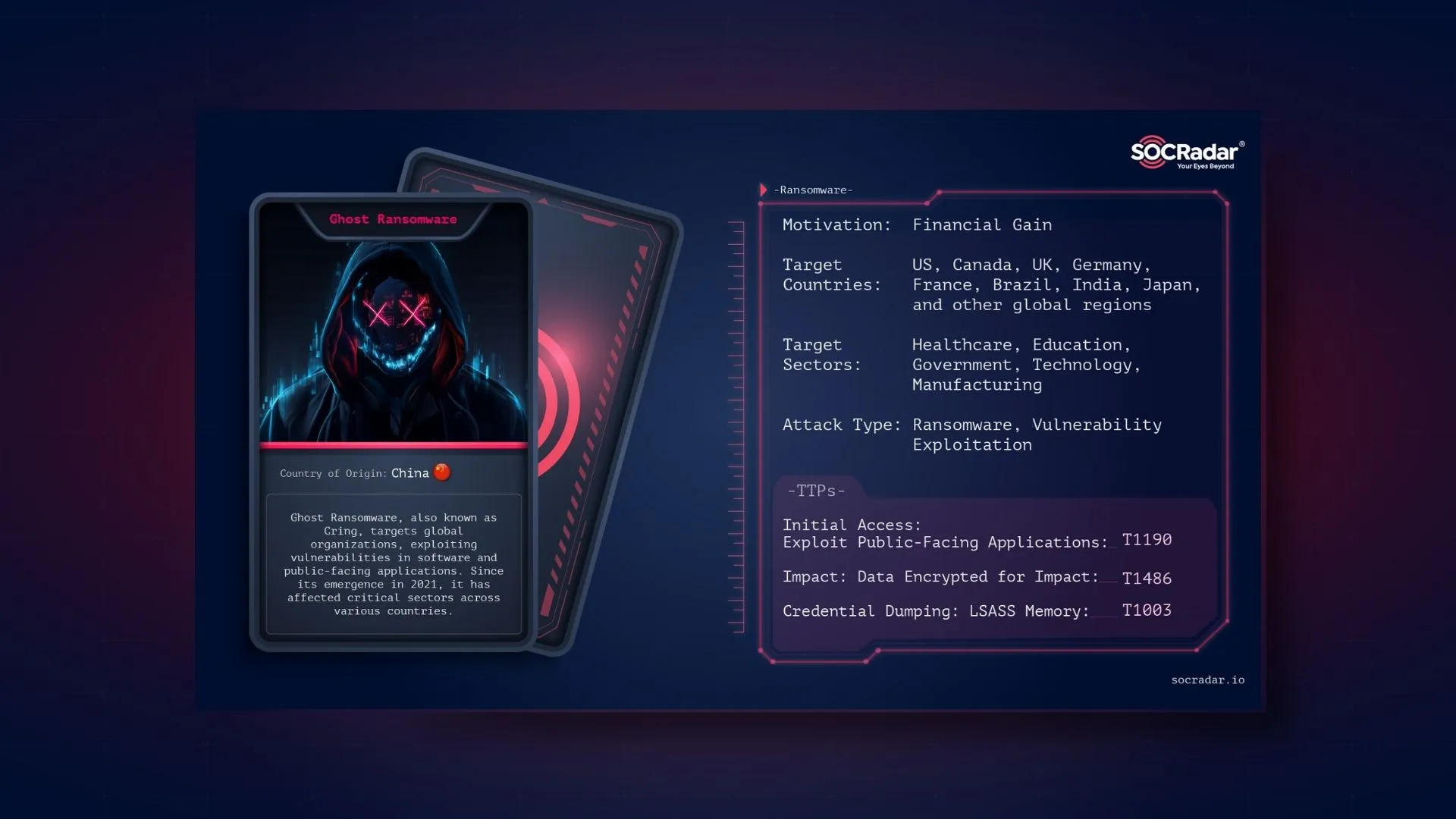

APT Profile: Turla

In the digital age, war has transitioned into the virtual world, where many types of cybercriminals, such as hacktivists and nation-state actors, are called Advanced Persistent Threats (APT) play a role in this type of war. Some of the APTs conduct “silent” campaigns of intrusion and destabilization during their attacks. These groups involved in cyber-espionage are redefining the landscape of security, aiming at critical infrastructures and confidential sectors across the globe. Among these, the Turla group, hailing from Russia, has set itself apart as a significant force. Turla group’s operations, impacting more than 45 countries, are as widespread as they are complex. This article delves into the profile of Turla, examining their attacks, attacking style, and the global effects of what they do.

Who is Turla?

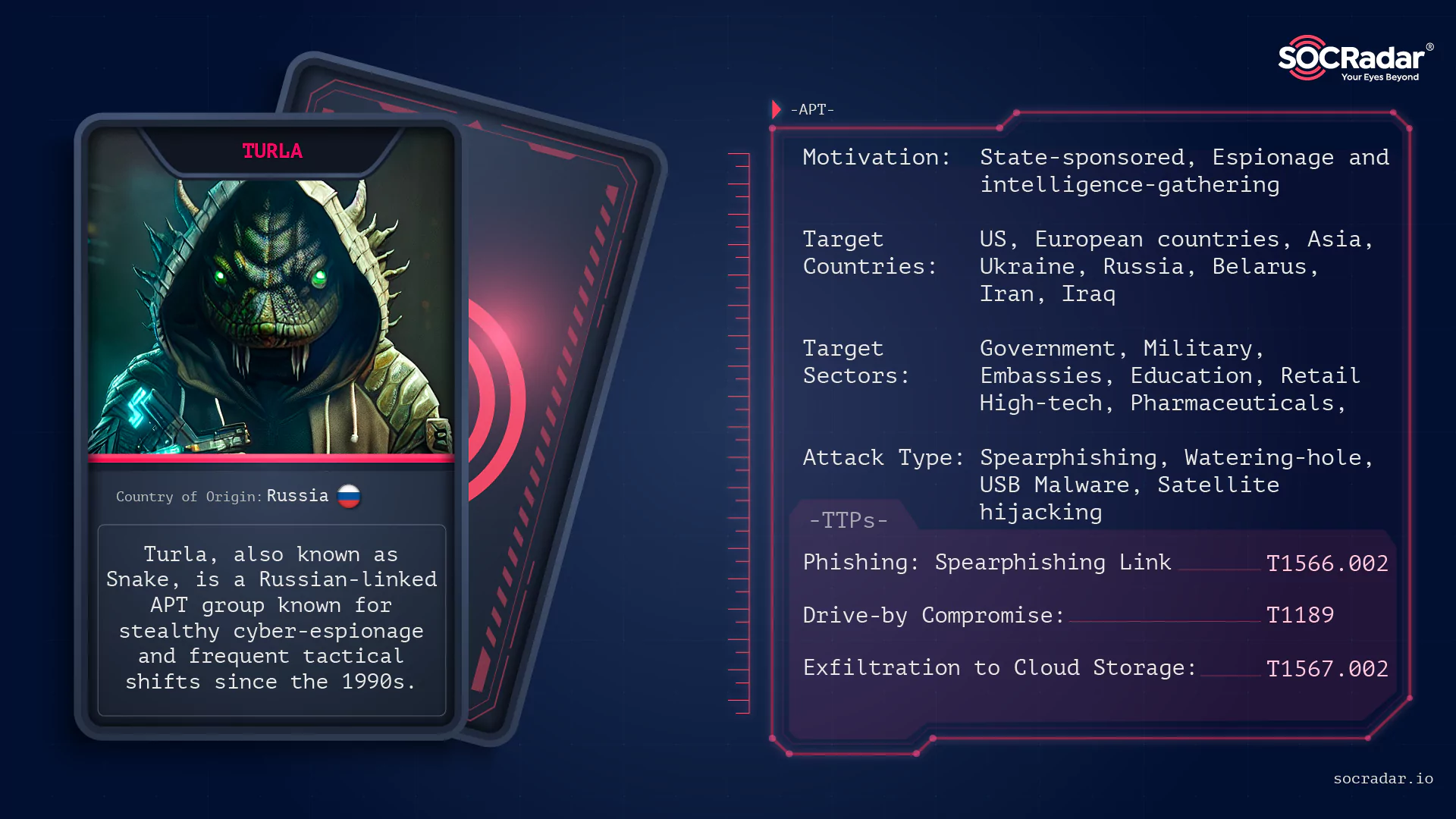

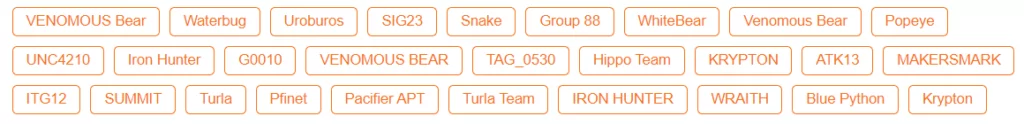

Turla, also known as Snake, UNC4210, Venomous Bear, Waterbug, or Uroburos, is a highly sophisticated APT group with espionage and intelligence-gathering motivations. The group has been active since the late 1990s. This group is believed to be one of the earliest examples of cyber espionage, with a primarily focus on government entities, militaries, and embassies.

Often linked to the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB), Turla has a long history of conducting cyber-espionage campaigns against a wide array of victims, spanning multiple sectors such as high-tech, pharmaceuticals, and retail. The group is known for its stealthiness and adaptability, frequently changing its tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) to evade detection and maintain persistence within its target networks.

How Does Turla Attack?

Turla employs a variety of attack vectors to gain initial access to its target systems. These include

- Spearphishing (T1566.001/002):Turla often uses spearphishing emails, containing malicious attachments or links, to trick unsuspecting users into downloading and executing malware. These emails are typically designed to appear as legitimate communications from trusted sources, increasing the likelihood that the recipient will interact with the malicious content.

- Watering hole attacks (T1189):This technique involves compromising legitimate websites that are frequented by the target organization’s employees. Once the website is compromised, Turla injects malicious code that exploits vulnerabilities in the visitor’s browser or extensions to gain a foothold on their system.

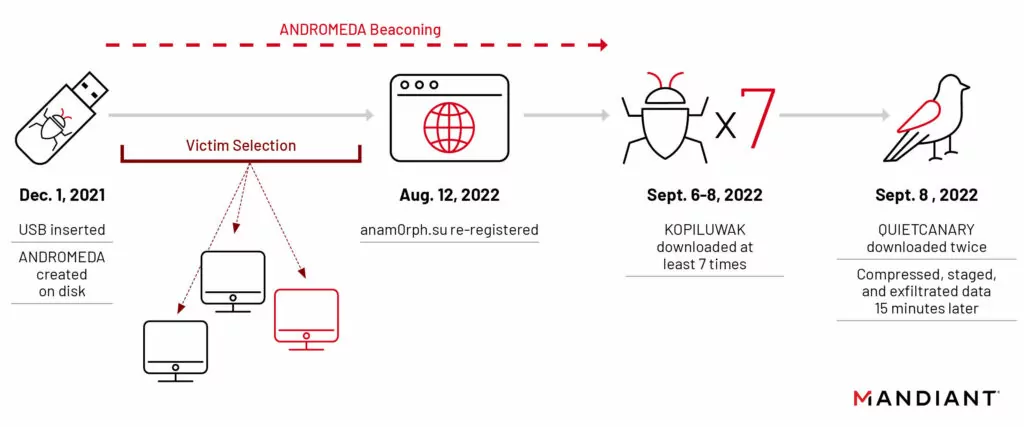

Turla uses a variety of sophisticated techniques to conduct their attacks. In one of its operations as an example, Turla was observed taking control of expired domains associated with widespread, financially motivated malware like ANDROMEDA. This approach allows them to deliver new malware to victims, enabling follow-on compromises. Turla has also been known to leverage USB spreading malware for gaining initial access into organizations.

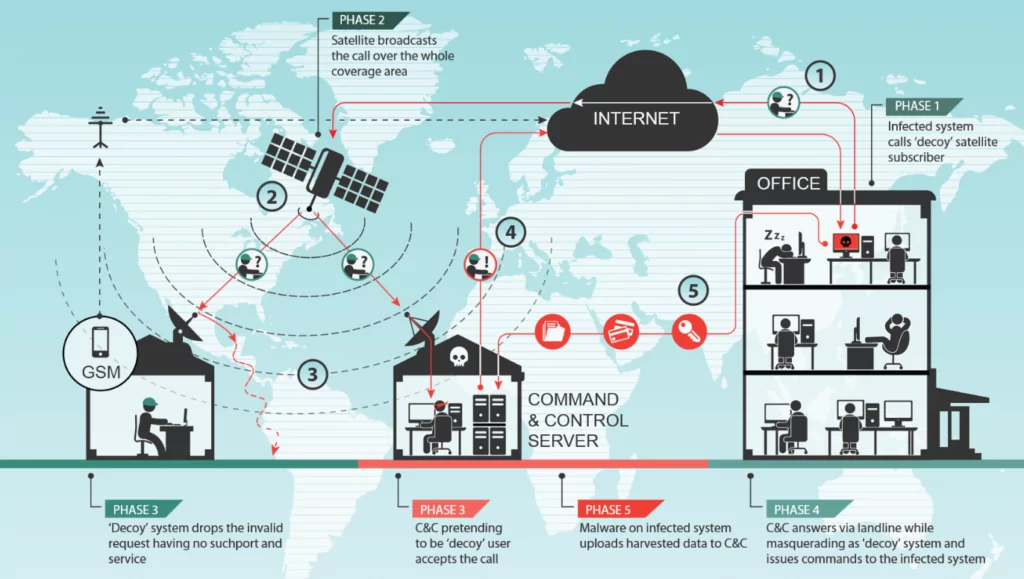

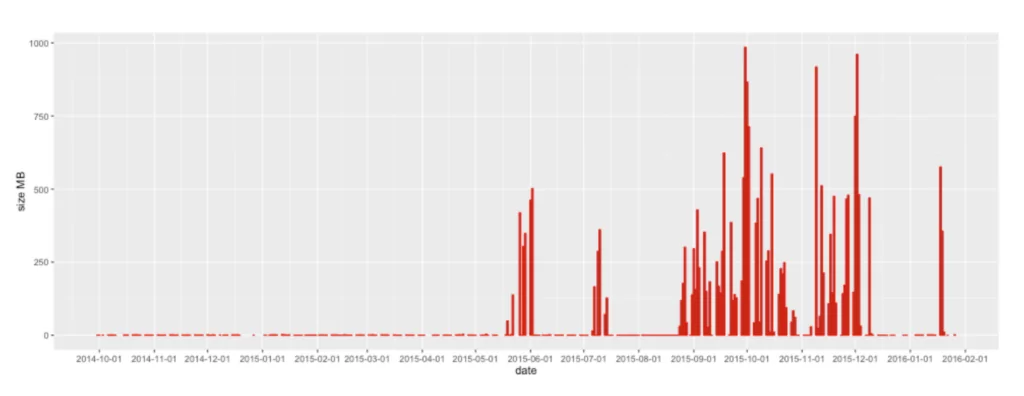

Adding to their sophistication and stealth, Turla was discovered in 2015 to be hijacking satellite communications to control their malware and exfiltrate data. By spoofing the IP address of a legitimate satellite internet subscriber, Turla could send their stolen data from compromised computers via satellite. An antenna connected to Turla’s command-and-control server could then pick up this broadcast data, leaving virtually no traces for investigators.

The group uses a combination of tools such as the KOPILUWAK reconnaissance utility and the QUIETCANARY backdoor. KOPILUWAK, a JavaScript-based utility, facilitates C2 communications and victim profiling, while QUIETCANARY is a lightweight .NET backdoor used primarily to gather and exfiltrate data from the victim.

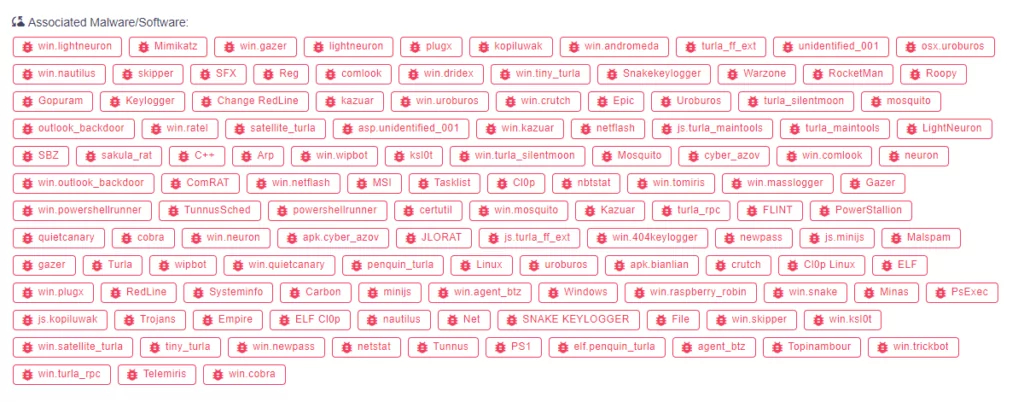

Which Tools and Vulnerabilities Does Turla Use?

Turla is known for using a wide range of custom-developed malware, as well as leveraging publicly available tools and exploiting known vulnerabilities to achieve its objectives. Some of the notable tools and vulnerabilities associated with Turla include:

- Agent.btz: Agent.btz is a computer worm that spreads primarily through removable devices like USB drives and is known for its significant breach of U.S. military networks in 2008.

- ComRAT: ComRAT, the new version of Agent.btz, is a Remote Access Trojan (RAT) used by the Turla APT group for cyber espionage. It is known for its unique feature of using the Gmail web interface for command and control operations.

- KopiLuwak:A JavaScript-based reconnaissance utility used to facilitate command and control (C2) communications and victim profiling. KopiLuwak has been observed in multiple Turla campaigns, often delivered via spearphishing emails or watering hole attacks.

- TunnusSched (QUIETCANARY): A backdoor used by Turla to maintain persistence and control over compromised systems. TunnusSched allows the attacker to execute arbitrary commands and has been linked to several Turla campaigns targeting government and military organizations.

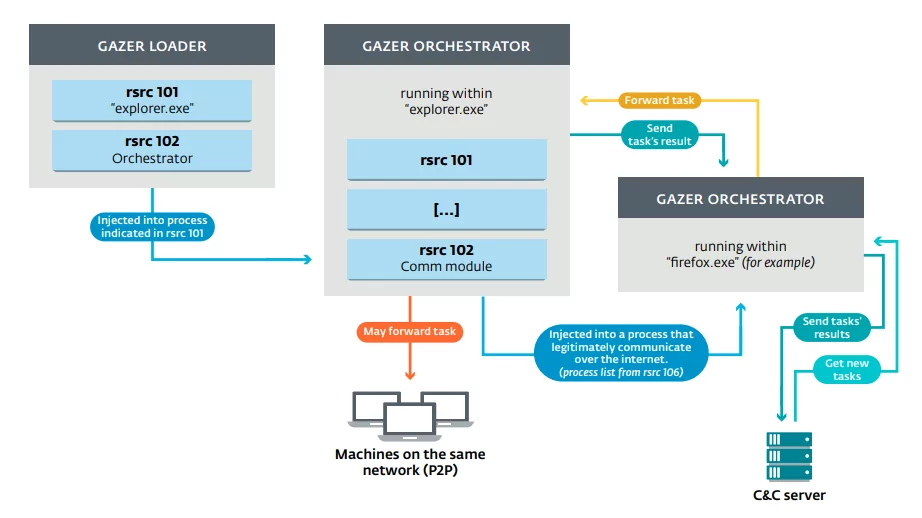

- Gazer: A sophisticated backdoor used by Turla that is known for its stealth and persistence capabilities. Gazer is designed to communicate with its C2 server using encrypted channels and can be customized with various plugins to extend its functionality.

- Carbon: A modular backdoor framework used by Turla, known for its advanced peer-to-peer capability and its ability to augment traditional command and control (C&C) infrastructure with tasks served from legitimate web services like Pastebin.

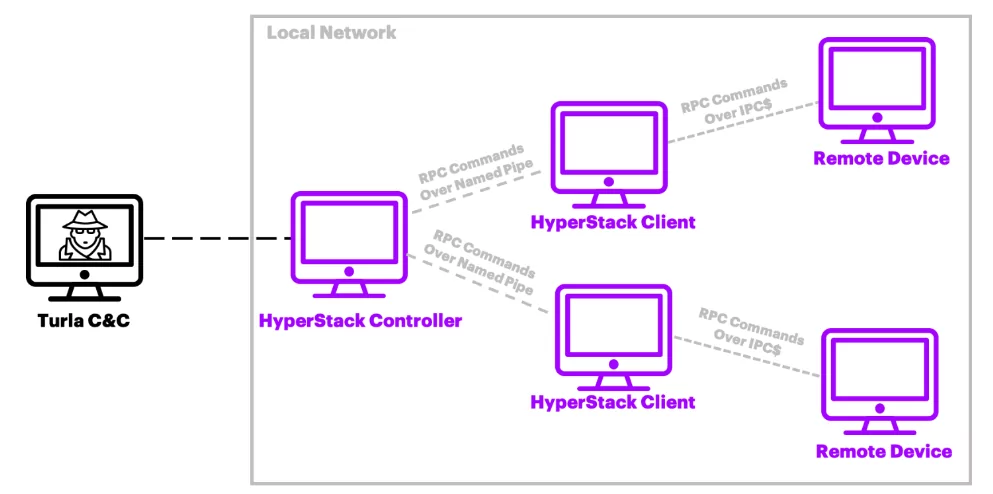

- HyperStack:A Remote Procedure Call (RPC) backdoor used by Turla, which uses named pipes for executing RPCs and maintains a custom handshake similar to Carbon’s named-pipe communications.

- Kazuar: A Remote Administration Trojan (RAT) used by Turla, configured to receive commands via internal C&C nodes in the victim’s network, while also capable of traditional C&C implementation with servers outside the victim network.

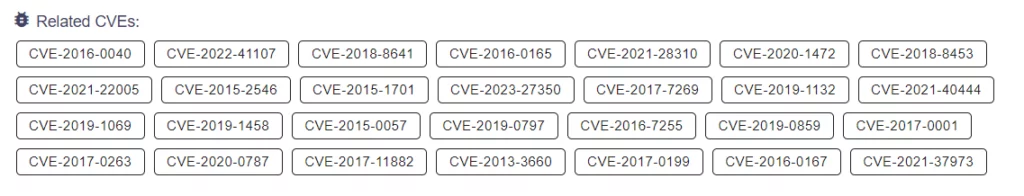

In addition to these custom tools, Turla has also been known to exploit various vulnerabilities in popular software, such as Microsoft Windows, Adobe Flash, and Oracle Java, to gain initial access and escalate privileges within target systems.

The fact that they have a wide-range toolset is evidenced by the fact that they have exploited so many CVEs over time

About the Malware ‘Snake’

Recently, the CISA published an advisory about a Russian Intelligence Malware “Snake”, It provides an in-depth analysis of the “Snake” implant, an advanced cyber espionage tool designed and used by Center 16 of Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) for long-term intelligence collection on sensitive targets.

The Snake implant operates through a covert peer-to-peer (P2P) network of Snake-infected computers worldwide. Many of these systems serve as relay nodes, routing operational traffic to and from Snake implants on the FSB’s ultimate targets. Snake’s custom communications protocols employ encryption and fragmentation to maintain confidentiality and are designed to hamper detection and collection efforts.

The advisory reveals that Snake infrastructure has been identified in over 50 countries across all continents, including the United States and Russia itself. The FSB has used Snake to collect sensitive intelligence from high-priority targets, such as government networks, research facilities, and journalists. For instance, FSB actors used Snake to access and exfiltrate sensitive international relations documents from a victim in a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) country.

The CISA provides detailed technical descriptions of the implant’s host architecture and network communications. It also addresses a recent Snake variant that has not yet been widely disclosed. The technical information and mitigation recommendations are provided to assist network defenders in detecting Snake and associated activity.

The report also delves into the history of Snake, noting that the FSB began developing Snake as “Uroburos” in late 2003. The developers left unique strings in the code, such as “Ur0bUr()sGoTyOu#”, which have publicly come back to haunt them. The report also mentions that the FSB has been quick to adapt Snake when its capabilities have been publicly disclosed by private industry, leading to several variants of Snake over almost 20 years.

The advisory also provides insights into the mistakes made by the FSB in the development and operation of Snake, which have provided researchers with a foothold into the inner workings of Snake and were key factors in the development of capabilities that have allowed for tracking Snake and the manipulation of its data.

What are the Targets of Turla?

Turla predominantly targets organizations in Ukraine. The group infiltrates a wide array of entities and conducts extensive victim profiling. This profiling allows the group to select specific victim systems and tailor their follow-on exploitation efforts to gather and exfiltrate information of strategic importance.

If categorized by sector and country:

Target Sectors of Turla:

Turla’s primary targets are government entities, militaries, and embassies. However, over the years, the group has expanded its operations to include victims from a wide range of sectors, including education, high-tech, pharmaceuticals, and retail.

Target Countries of Turla:

Turla’s victims are located across the globe, with a particular focus on countries in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. Some of the countries that have been targeted by Turla include France, Romania, Kazakhstan, Poland, Tajikistan, Austria, Russia, the United States, Saudi Arabia, Germany, India, Armenia, Belarus, the Netherlands, Iran, Uzbekistan, and Iraq.

A Quick Look to Turla APT Group’s Operations and Notable Activities:

Turla has been linked to several high-profile cyber-espionage campaigns, including:

- Moonlight Maze: The Moonlight Maze operation, which started around 1996 and lasted for at least two years, is considered one of the first cyber espionage campaigns that targeted the United States. During this period, the hackers successfully breached various US government systems, including the US Navy, Air Force, NASA, the Department of Energy, the Environment Protection Agency, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The hackers used a modified version of a tool known as Loki2, which they consistently updated over time.

In 2016, researchers established a connection between this tool and Turla, leading to the inference that Moonlight Maze was likely an early operation of what would later become Turla.

- Agent.btz: In 2008, Turla launched a significant attack on the United States Department of Defense with malware known as Agent.btz. This malware was discovered beaconing out from inside the classified network of the DOD’s US Central Command, which was supposed to be air-gapped and physically isolated from internet-connected networks. The malware had spread from USB thumb drives, though it remains unclear how the infected USB devices infiltrated the US military’s digital inner sanctum. This breach led to a multiyear initiative to revamp US military cybersecurity, a project called Buckshot Yankee, and the creation of US Cyber Command.

- The Epic Turla: The Epic Turla Operation was a global, multifaceted cyber espionage campaign that primarily targeted Eastern Europe, demonstrating a range of sophisticated attacking patterns. The operation utilized a variety of tactics, including the “watering hole” attack, where hackers compromised websites their targets frequently visit. They also employed spearphishing, sending malicious emails to specific individuals or organizations. Turla exploited zero-day vulnerabilities, such as CVE-2013-5065 (Windows XP and Windows 2003 Privilege escalation vulnerability), and CVE-2013-3346 (Arbitrary code-execution vulnerability in Adobe Reader), to gain unauthorized access to systems, utilizing the flaws in software unknown to the developers. Once infiltrated, various forms of malware, including a rootkit and a backdoor, were deployed to maintain control over the systems and exfiltrate sensitive data, showcasing the complexity and intricacy of this long-term cyber espionage campaign.

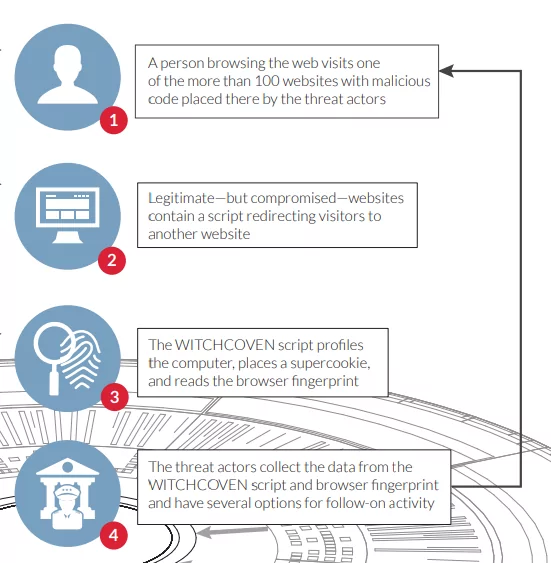

- Witchcoven: A threat actor group compromised over 100 “specifically selected” websites in a cyber espionage operation in 2015. The group, possibly linked to the Turla or Turla itself, used web analytics and open-source tools to collect data about potential victims and their devices. The attackers injected a small piece of code, dubbed “WITCHCOVEN”, into the compromised websites, which collects the victim’s computer and browser configuration and deploys a persistent tracking cookie called “supercookie”. The data collected is believed to be used to create spearphishing emails, build user profiles for espionage, and create a database of potential targets.

The campaign targeted individuals interested in international travel, diplomacy, economics, energy production and policy, and government affairs.

- RUAG Espionage Incident: In 2016, Swiss defense company RUAG was targeted by Turla in a sophisticated cyber-espionage campaign that resulted in the theft of sensitive data related to Swiss military technology.

Is There a Relation Between Turla APT Group and Other Cyber-espionage Groups?

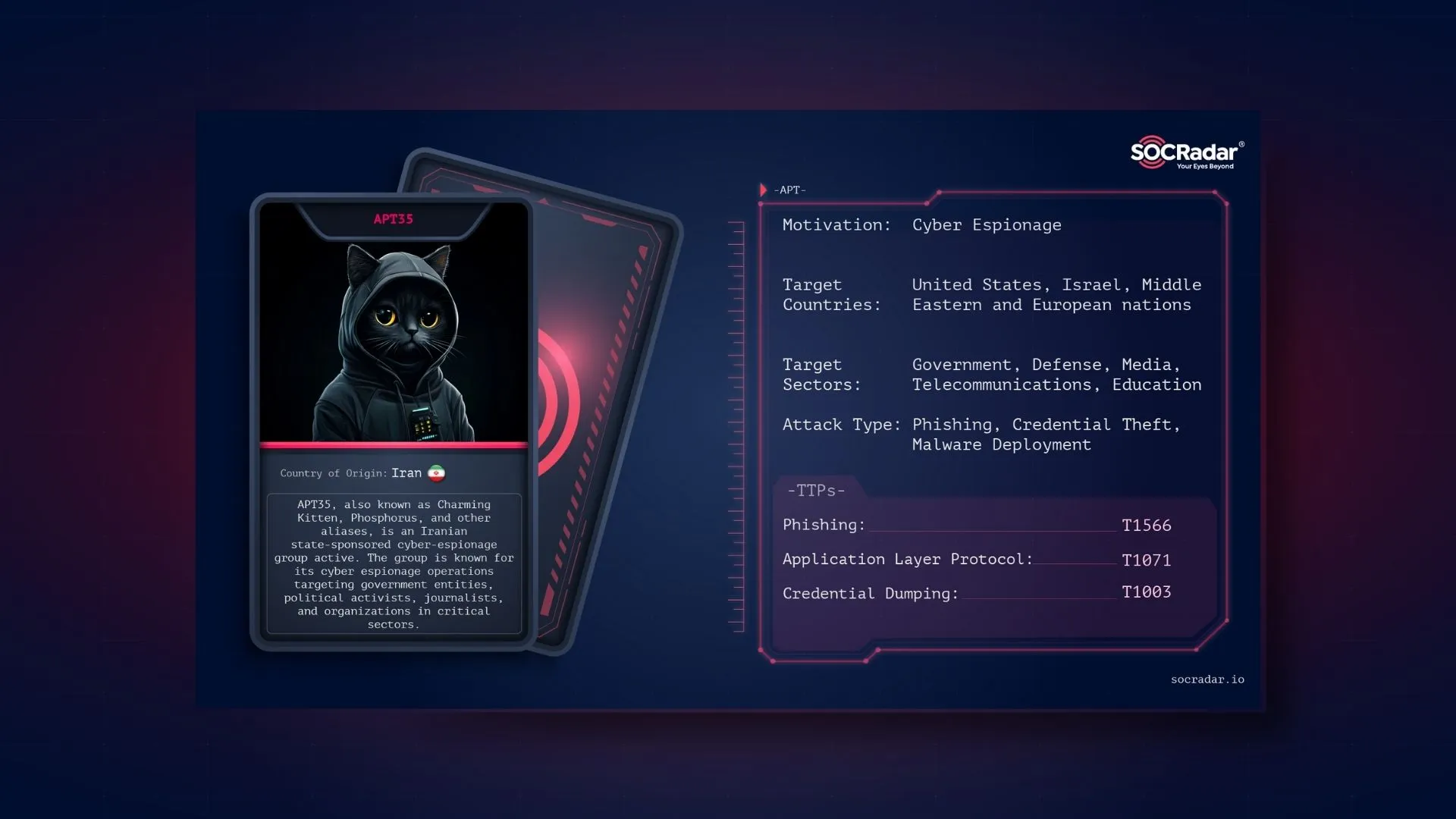

Iranian APT Groups:

The UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) disclosed in 2019 that the Neuron and Nautilus tools, which were previously believed to be connected to Turla, were actually likely of Iranian origin. They found that Turla had taken control of these tools and mainly used them against targets located in the Middle East. The NCSC also revealed that Turla employed Iranian web shells and used PoisonFrog C2 control panels, originally associated with COBALT GYPSY (APT34), to disseminate its malicious software.

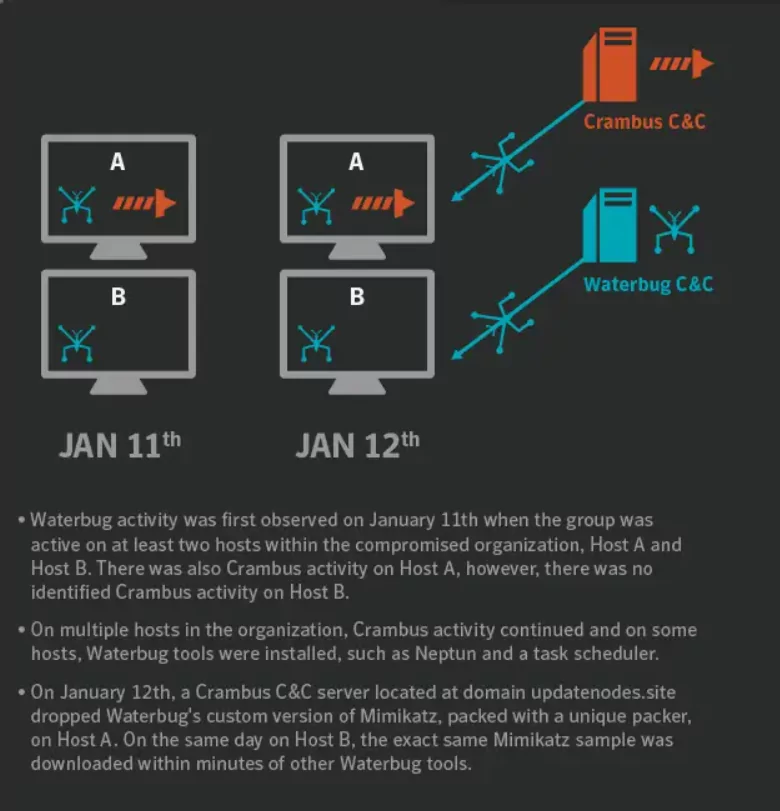

According to another source, during one attack against a Middle Eastern target, Turla appeared to hijack the infrastructure (C2) of Iranian APT group Crambus (APT34) and used it to deliver malware onto the victim’s network. This is unusual because these two groups have been linked to different nation states, and there’s no evidence to suggest they were collaborating. The motive behind Turla’s use of Crambus’s infrastructure is unclear. It could have been a false flag operation, a means of intrusion, or an opportunistic move to sow confusion.

Tomiris

The Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) groups, Tomiris and Turla, are distinguished by their unique Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs), but overlapping characteristics have confused cybersecurity researchers. Kaspersky’s analysts found that Tomiris had been behind certain attacks previously attributed to Turla.

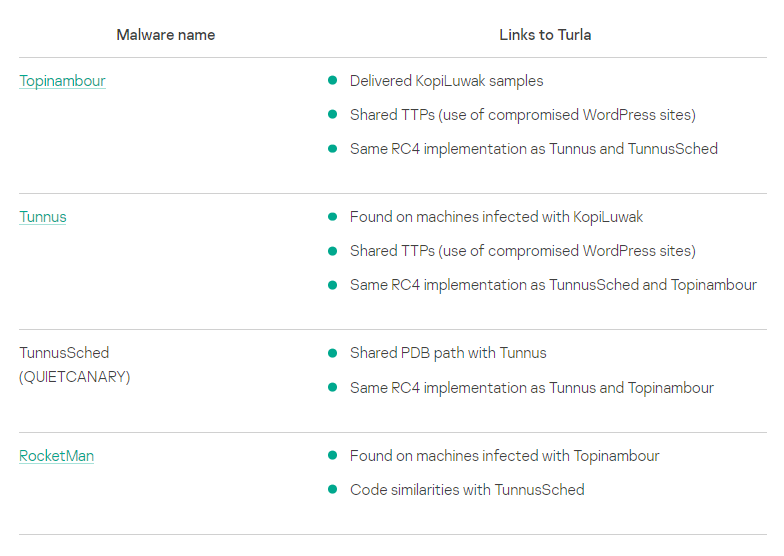

In an intriguing turn of events between 2021 and 2023, Tomiris demonstrated using Turla’s malicious tools, namely the JavaScript-based KopiLuwak payload and the TunnusSched scheduler. This overlapping tool usage led researchers to speculate potential collaboration or information sharing between these groups, although the exact nature of their relationship is still unclear.

Turla remains an active and formidable threat in the world of cyber-espionage, with a long history of successful campaigns against high-value targets. The group’s adaptability, stealth, and persistence make it a dangerous adversary that is likely to continue targeting organizations worldwide.

Understanding this snake in the grass is the first step in avoiding its bite. By following the recommended security steps below, organizations can better protect their digital assets and ensure that their sensitive information remains secure.

Security Recommendations Against Turla

To defend against Turla and other sophisticated threat actors, organizations should take the following steps:

- To defend against Turla and similar APTs, organizations should adopt a proactive approach that includes Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI). CTI involves the collection and analysis of information about potential or current attacks threatening an organization and industry.

- Implementing security awareness training to employees, focusing on the tactics and techniques used by Turla and other APT groups to help users identify and report suspicious content.

- Employ the latest intrusion detection and prevention systems (IDS/IPS) and Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) solutions to monitor network traffic and endpoint behavior for signs of malicious activity. Block access to known malicious domains, hosts, and IP addresses.”

- Regularly patch and update software to minimize the attack surface and reduce the risk of exploitation.

- Implement “multi-factor authentication (MFA)” and strong password policies to protect user accounts from unauthorized access.

- Establish a comprehensive incident response plan and practice it regularly to ensure that your organization is prepared to respond effectively in the event of a breach.

By implementing these measures and staying informed about the latest developments in cyber threat intelligence, organizations can better protect themselves against the ever-evolving threat landscape posed by Turla and other advanced persistent threat groups.