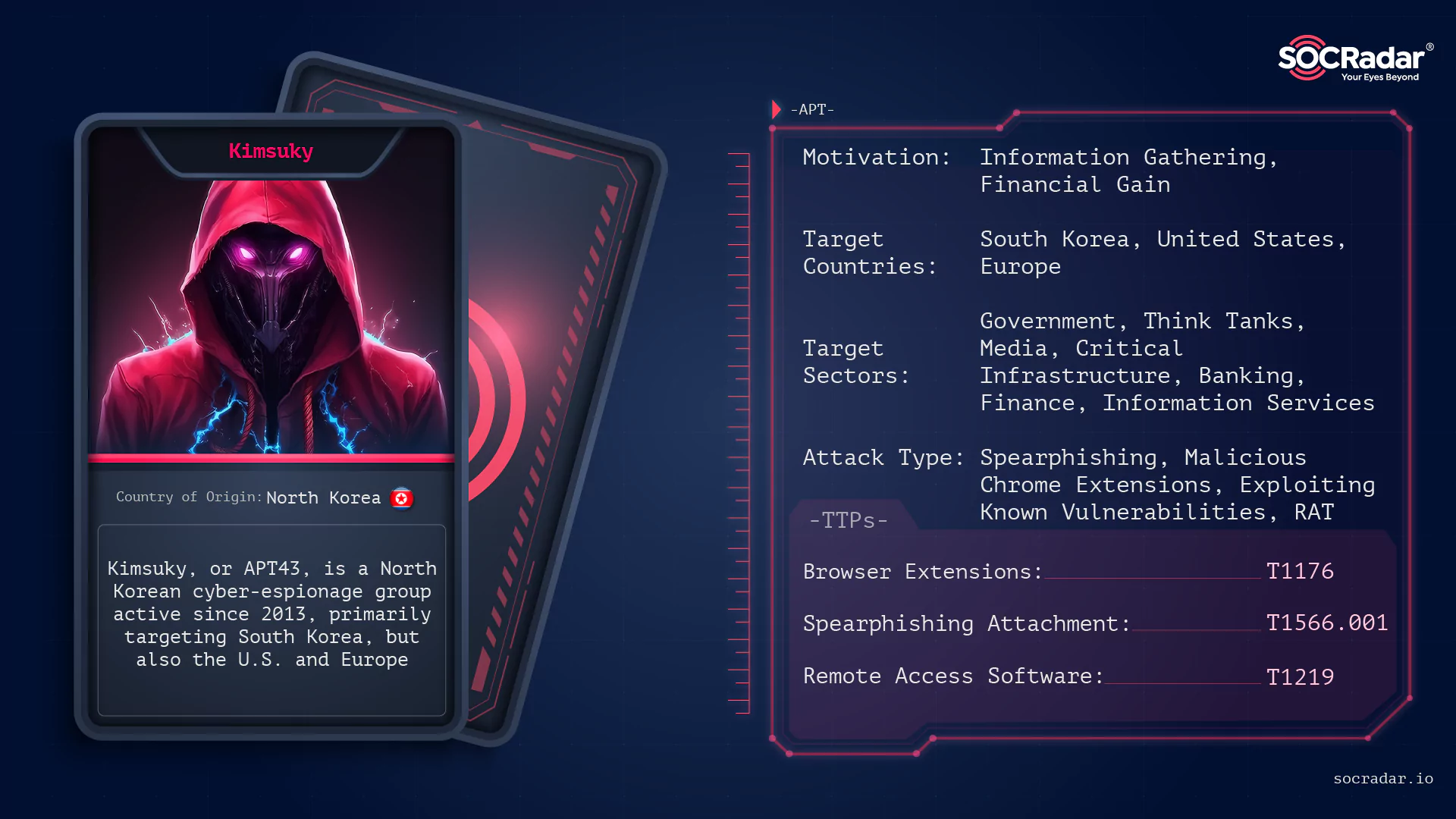

APT Profile: Kimsuky

[Update] December 2, 2024: “Kimsuky’s Phishing Evolution and the Threat of Malwareless Attacks”

In cyberspace, the Korean Peninsula has been a hotbed of activity for a while. With conflict unfolding between North and South Korea, North Korean Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) are emerging as the weapon of choice. Among these, one name stands out: Kimsuky.

North Korean APTs have been responsible for some of the most audacious cyber-attacks in recent history. According to a United Nations report, North Korean hackers have pilfered over $2 billion through cyber-attacks on banks and cryptocurrency exchanges. These funds are believed to be channeled into North Korea’s weapons programs.

Enter Kimsuky, a North Korean APT group that has been operating for a while and recently started to be heard in the media again. But what makes Kimsuky this famous?

This blog post aims to shed light on Kimsuky, providing an in-depth profile of this threat actor. We will explore who they are, how they operate, the tools and vulnerabilities they exploit, their targets, and their operations. We will also provide some security recommendations to help protect against Kimsuky’s attacks. Understanding the threat posed by Kimsuky is the first step towards building a robust defense against cyber-espionage activities.

Who is Kimsuky?

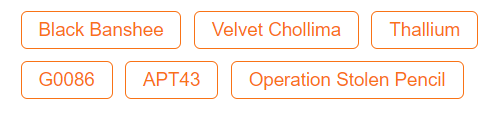

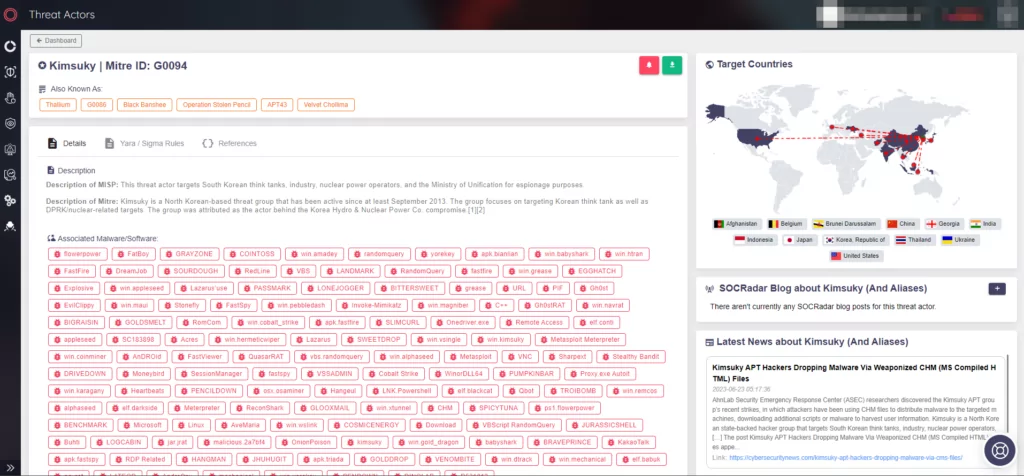

Kimsuky (or APT43), a name that sends tides through the cybersecurity community, is a cyber-espionage group believed to be operating out of North Korea. First observed in 2013, Kimsuky has been determined to pursue sensitive information, primarily focusing on South Korea and extending its reach to the United States and Europe.

How Does Kimsuky Attack?

Kimsuky employs a range of tactics to infiltrate systems and gathers sensitive information. Let’s break down their modus operandi:

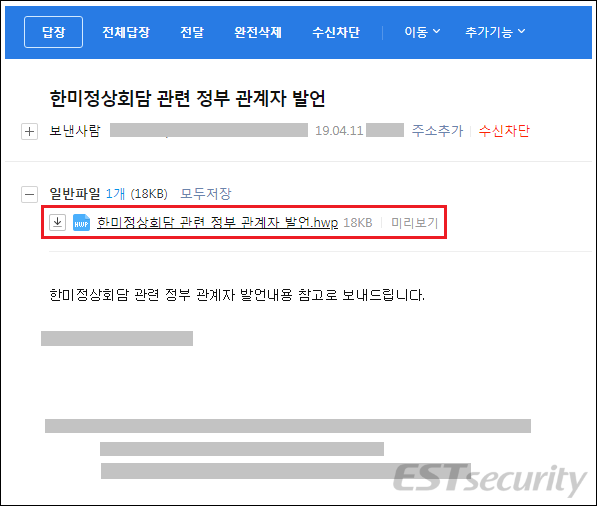

Spearphishing Emails

One of the primary methods Kimsuky uses to gain unauthorized access to systems is through spearphishing emails. These are targeted emails sent to specific individuals or organizations. The emails often contain malicious attachments or links. For example, Kimsuky has been known to use Hangul Word Processor (HWP) files, which are popular in South Korea. These files contain exploits for known vulnerabilities or a dropper disguised as a document.

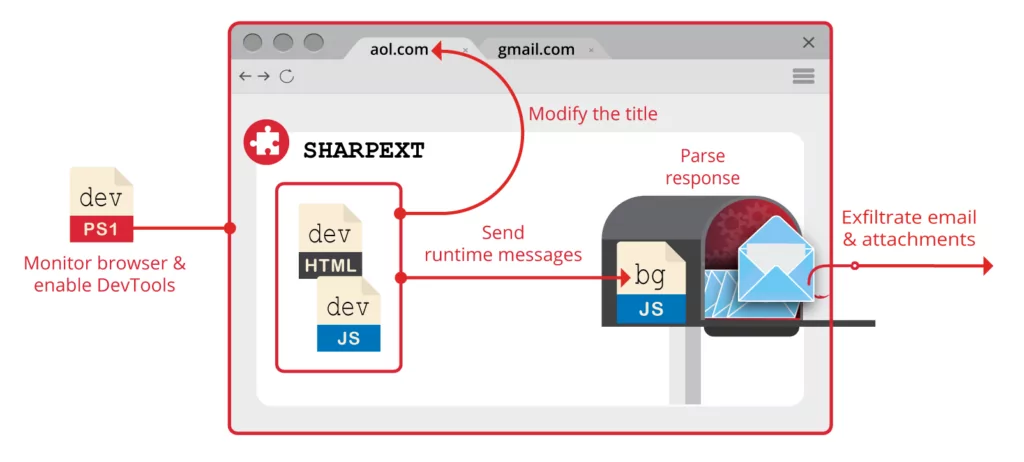

Malicious Chrome Extensions

Kimsuky has also been observed using malicious Google Chrome extensions to infect victims. They lure victims to websites that appear legitimate and prompt them to install a Chrome extension. Once installed, this extension can steal cookies and passwords from the browser.

Exploiting Vulnerabilities

Kimsuky is known for exploiting known vulnerabilities in software. For instance, they have exploited a vulnerability in Microsoft Word (CVE-2017-0199) to execute malicious code. By keeping an eye on newly discovered vulnerabilities and exploiting them before they are patched, Kimsuky can gain access to systems with minimal detection.

Use of Malware

Once Kimsuky has gained access to a system, they deploy malware to maintain control. One such malware is BabyShark, which is used to gather data from the infected system. They also use keyloggers and remote control software to monitor the user’s actions and gather further information.

Kimsuky’s attacks are well-planned and executed with precision. Their ability to use a combination of spearphishing, exploiting vulnerabilities, and deploying malware makes them a formidable threat.

Which Tools and Vulnerabilities Used by Kimsuky?

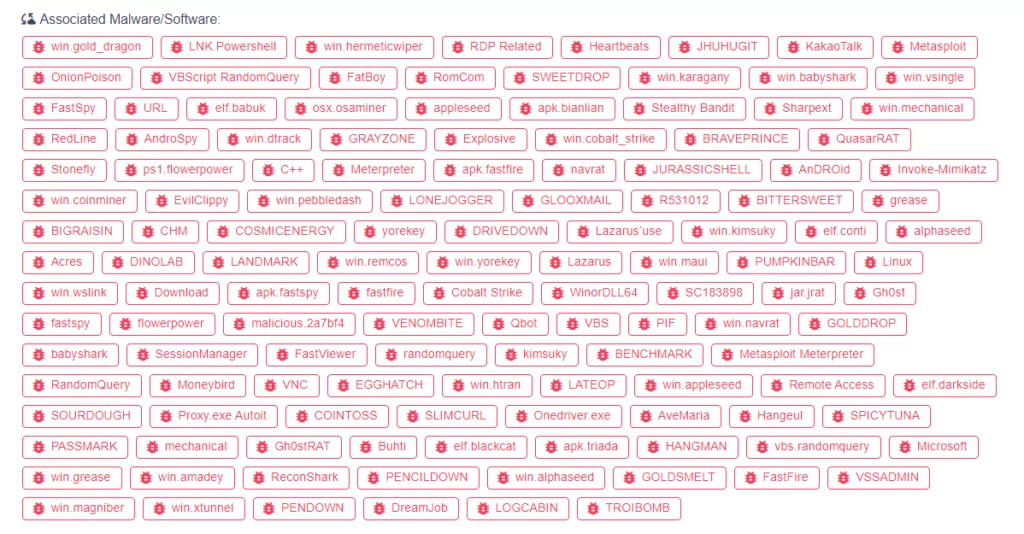

Kimsuky employs a variety of tools and exploits several vulnerabilities to carry out its cyber espionage campaigns. Here’s a closer look:

Tools Used by Kimsuky:

Kimsuky’s toolkit is extensive and varied, reflecting a high degree of sophistication and adaptability. Their ability to exploit a range of vulnerabilities and deploy a diverse set of tools makes them a formidable and persistent threat.

BabyShark Malware

One of the prominent tools in Kimsuky’s arsenal is the BabyShark malware. This malware is used to collect data from infected systems. It is often delivered through spearphishing emails as a second-stage payload.

Gold Dragon

Gold Dragon, a data-gathering tool that was first seen in December 2017 during a spearphishing campaign in Korea targeting the same Olympic-linked organizations. The tool has observed that it was used in operations aimed at entities connected to the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics.

As a second-stage backdoor implant, Gold Dragon ensured a lasting presence on the victim’s system after the execution of a file-less, PowerShell-based initial attack that used steganography.

The capabilities of this malware included basic reconnaissance, data extraction, and the ability to download additional components from its command and control server.

SWEETDROP

SWEETDROP is a malware dropper that is actively used by Kimsuky during the Covid-19 pandemic. It is a C/C++ Windows application that collects basic system information and is capable of downloading and executing additional stages such as download and execution of Kimsuky’s backdoor “BITTERSWEET”.

Vulnerabilities Exploited by Kimsuky:

Kimsuky’s use of these tools and exploitation of vulnerabilities demonstrates their adaptability and resourcefulness. They are capable of using both custom and off-the-shelf tools to achieve their objectives.

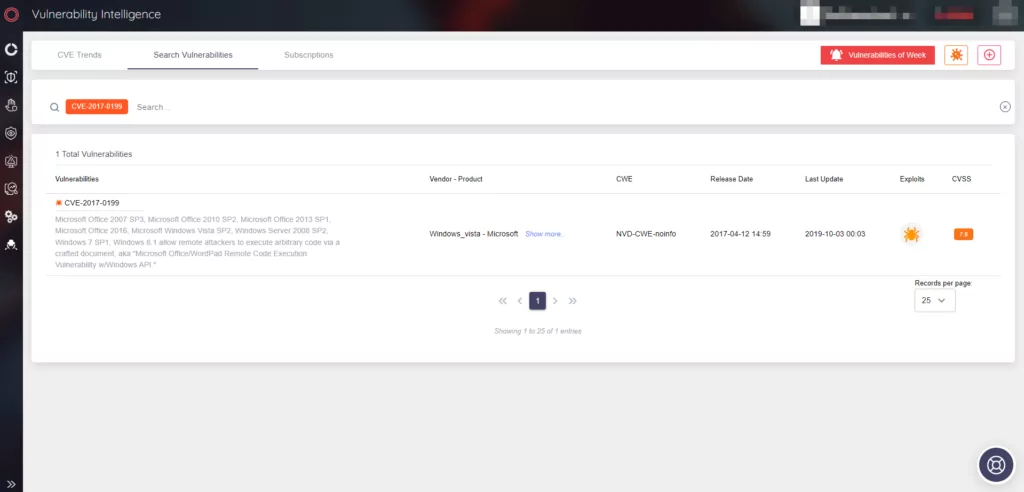

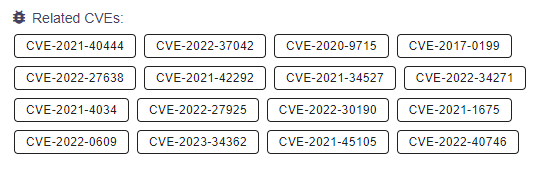

CVE-2017-0199

Kimsuky exploited this vulnerability to deliver the BabyShark malware. This is a vulnerability in Microsoft Word that allows a specially crafted file to execute code.

HWP Exploits

Hangul Word Processor (HWP) files are widely used in South Korea. Kimsuky has been known to use HWP files that contain exploits for known vulnerabilities to install droppers on systems.

CVE-2015-2545

This is a vulnerability in Microsoft Office that allows for remote code execution through specially crafted EPS image files. Kimsuky has exploited this vulnerability to execute malicious code and install malware on target systems.

CVE-2019-0604

Kimsuky has exploited this vulnerability in Microsoft SharePoint to execute arbitrary code. By sending a specially crafted SharePoint application package, attackers can run arbitrary code in the context of the SharePoint application pool and the SharePoint server farm account.

What are the Targets of Kimsuky?

Kimsuky mainly targets South Korean think tanks, industry, nuclear power operators, and the Ministry of Unification for espionage purposes.

Targeted Sectors

Kimsuky’s cyber-espionage campaigns are highly targeted. They focus on specific sectors and countries that align with the strategic interests of North Korea. The most targeted industries by Kimsuky are:

- Government Institutions,

- Think Tanks and Academic Institutions,

- Media Outlets (Publishing Services),

- Critical Infrastructure (Energy & Utilities, Space & Defence, National Security&International Affairs),

- Cryptocurrency & NFT (Banking, Finance),

- Information Services

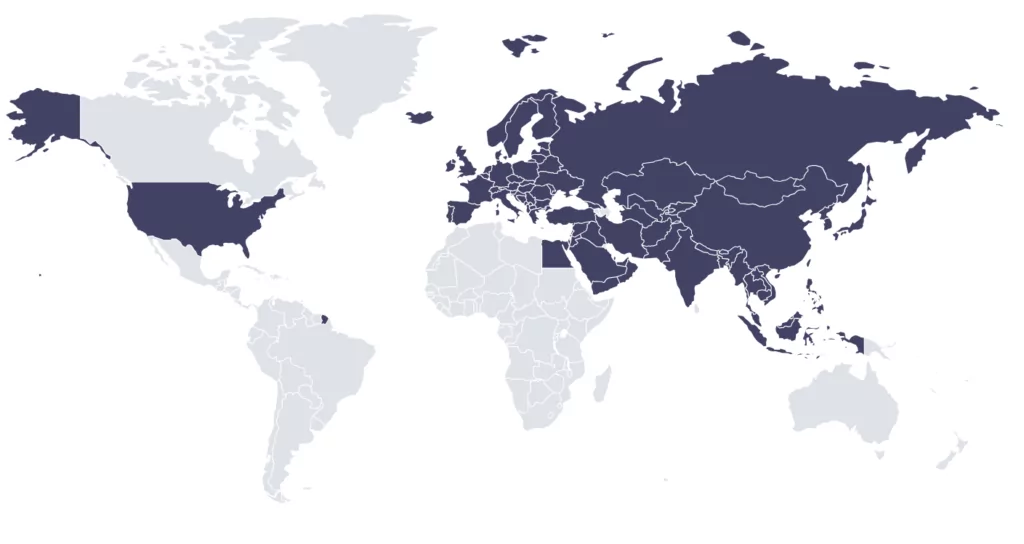

Targeted Countries

Kimsuky’s activities are believed to align with North Korea’s foreign intelligence agency, the Reconnaissance General Bureau (RGB), and the group’s main targets are mostly:

- South Korea

- United States

- European Countries

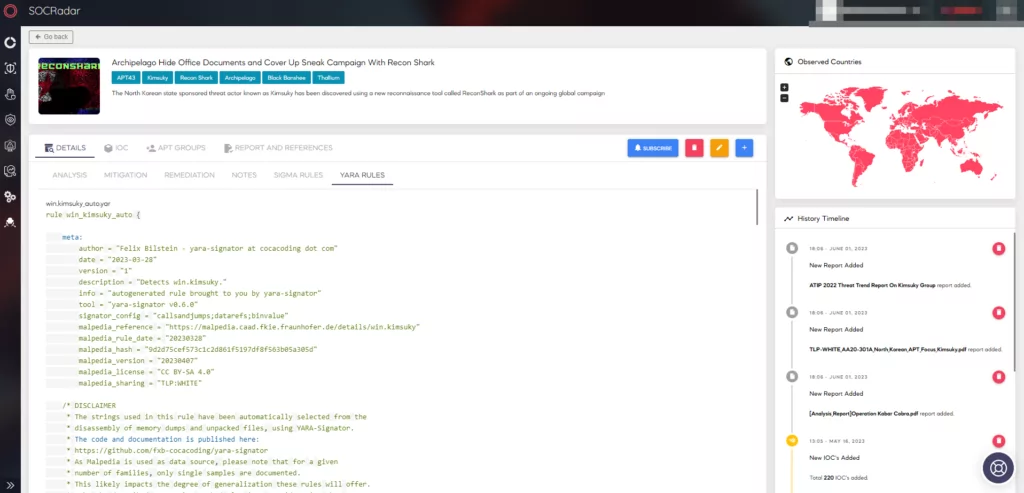

Operations of Kimsuky

Kimsuky has been involved in several distinct operations, each with specific targets and objectives. Here are some of the notable operations attributed to Kimsuky:

South Korean Nuclear Reactor Cyberattack

Timeframe: December 2014

In this operation, Kimsuky was implicated in cyberattacks against South Korea’s nuclear reactor operator. The attack raised concerns about critical infrastructure security and highlighted the extent of Kimsuky’s capabilities.

Operation Stolen Pencil

Timeframe: Active since at least May 2018

Operation Stolen Pencil was a campaign that targeted academic institutions. Kimsuky used spearphishing emails to lure victims to websites that appeared to be legitimate academic organizations. The victims were then prompted to install a malicious Google Chrome extension. This extension was capable of stealing cookies and passwords from the browser.

Foreign Ministries and Think Tanks Spearphishing Campaign

Timeframe: Late 2018

Kimsuky conducted a spearphishing campaign targeting multiple foreign ministries and think tanks. The spearphishing emails contained malicious Microsoft Word documents that exploited a known vulnerability (CVE-2017-0199) to download and execute the BabyShark malware. The targets included the United Nations Security Council, the U.S. Department of State, and several think tanks based in the U.S. and Europe.

Operation AppleSeed

Timeframe: 2021

In this operation, Kimsuky was observed distributing a backdoor known as AppleSeed. The group used spearphishing emails to target South Korean government agencies. The emails contained malicious attachments that, when opened, would install the AppleSeed backdoor on the victim’s system. This backdoor allowed Kimsuky to exfiltrate data and execute commands remotely.

Operation CloudDragon

Timeframe: 2023

Recently, Kimsuky has been linked to a new campaign dubbed Operation CloudDragon. This operation involves the use of social engineering, spearphishing, and custom malware to target think tanks, news media, and experts on North Korean affairs. Kimsuky impersonated journalists and used spoofed URLs, and weaponized Office documents to steal credentials and gather strategic intelligence.

Emulating Kimsuky’s Espionage Operations

Timeframe: April 2023

AttackIQ released four new attack graphs that emulate the espionage activities of Kimsuky. This politically motivated North Korean adversary has been involved in sophisticated espionage operations, and the attack graphs provide insights into their tactics and techniques.

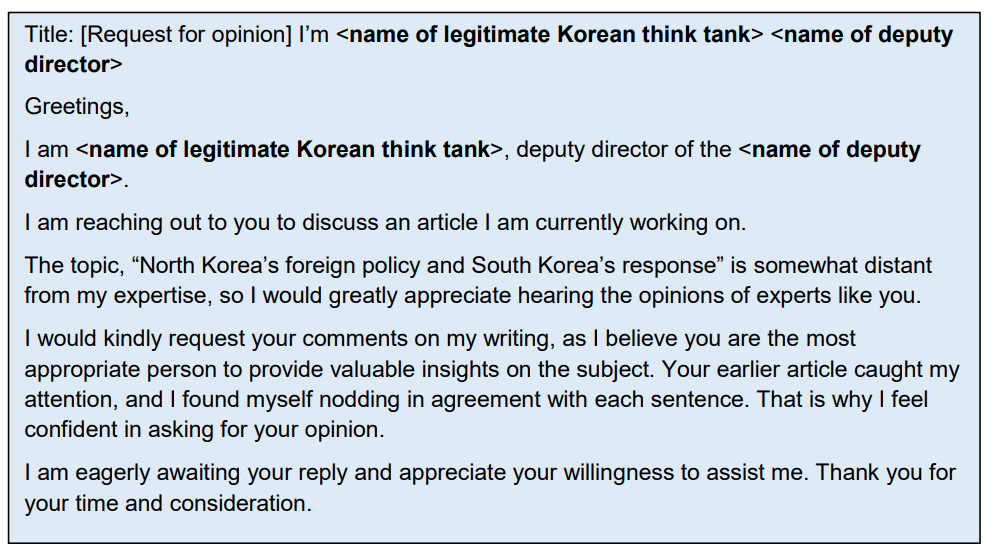

Social Engineering and Spearphishing Campaigns

Timeframe: June 2023

According to a joint Cybersecurity Advisory by U.S. and Republic of Korea (ROK) agencies, Kimsuky has been involved in social engineering campaigns targeting think tanks, academia, and news media. The advisory provides detailed information on how Kimsuky actors operate and warning signs of spearphishing campaigns. North Korea relies heavily on intelligence gained from these operations. Kimsuky has been involved in impersonation campaigns and has been targeting governments, political organizations, and more for intelligence collection.

These recent operations highlight Kimsuky’s ongoing efforts to gather intelligence and the evolving nature of their tactics.

Connections with Other APT Groups

Kimsuky is one of several APT groups believed to be operating out of North Korea. While Kimsuky operates independently, there are indications that it may have connections with other North Korean APT groups.

Lazarus

One such group is the Lazarus Group, which is known for its global cyber espionage and cybercrime campaigns. The Lazarus Group has been implicated in high-profile attacks, including the Sony Pictures hack in 2014 and the WannaCry ransomware attack in 2017.

While there is no direct evidence linking Kimsuky to the Lazarus Group, both groups share similarities in their tactics and targets. Additionally, both groups are believed to be sponsored by the North Korean government, which suggests that they may share resources or information.

APT37 (Reaper)

Another North Korean APT group, known as APT37 or Reaper, has been active since at least 2012. Like Kimsuky, APT37 has primarily targeted South Korea but has also conducted operations against Japan, Vietnam, and the Middle East. APT37 is known for using zero-day vulnerabilities and malware in its cyber-espionage campaigns.

Again, while there is no concrete evidence of direct collaboration between Kimsuky and APT37, the similarities in their targets and tactics suggest that they may be part of a coordinated effort by the North Korean government to conduct cyber espionage.

In summary, Kimsuky, while operating independently, is part of a larger ecosystem of North Korean APT groups. The shared tactics, targets, and likely state sponsorship suggest that these groups may be loosely connected or at least aligned in their objectives.

Some of the samples’ strings contain the “Kim” keyword:

- “kimm.r-naver[.]com”,

- “kimsukyang and Kim asdfa” the owner of “iop110112@hotmail[.]com and rsh1213@hotmail[.]com domains extracted in one of the first observations.

- And other IoCs contain “tjkim”, “kimyfrenotsure”, “kimshan”, “Kim_Summit”, etc.

These and similar IoCs can be found on the Kimsuky Threat Actor page on SOCRadar XTI’s Cyber Threat Intelligence Module

So, it is also possible to conclude from these IoCs that Kimsuky is a separate threat actor and that it stands out from other North Korean threat actors.

Kimsuky’s Phishing Evolution and the Threat of Malwareless Attacks

Recent investigations reveal that Kimsuky has refined its phishing tactics, introducing malwareless attacks to evade Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) solutions. These campaigns primarily target researchers and organizations focusing on North Korean issues, exploiting urgency-driven themes like financial deadlines and official alerts to compromise accounts.

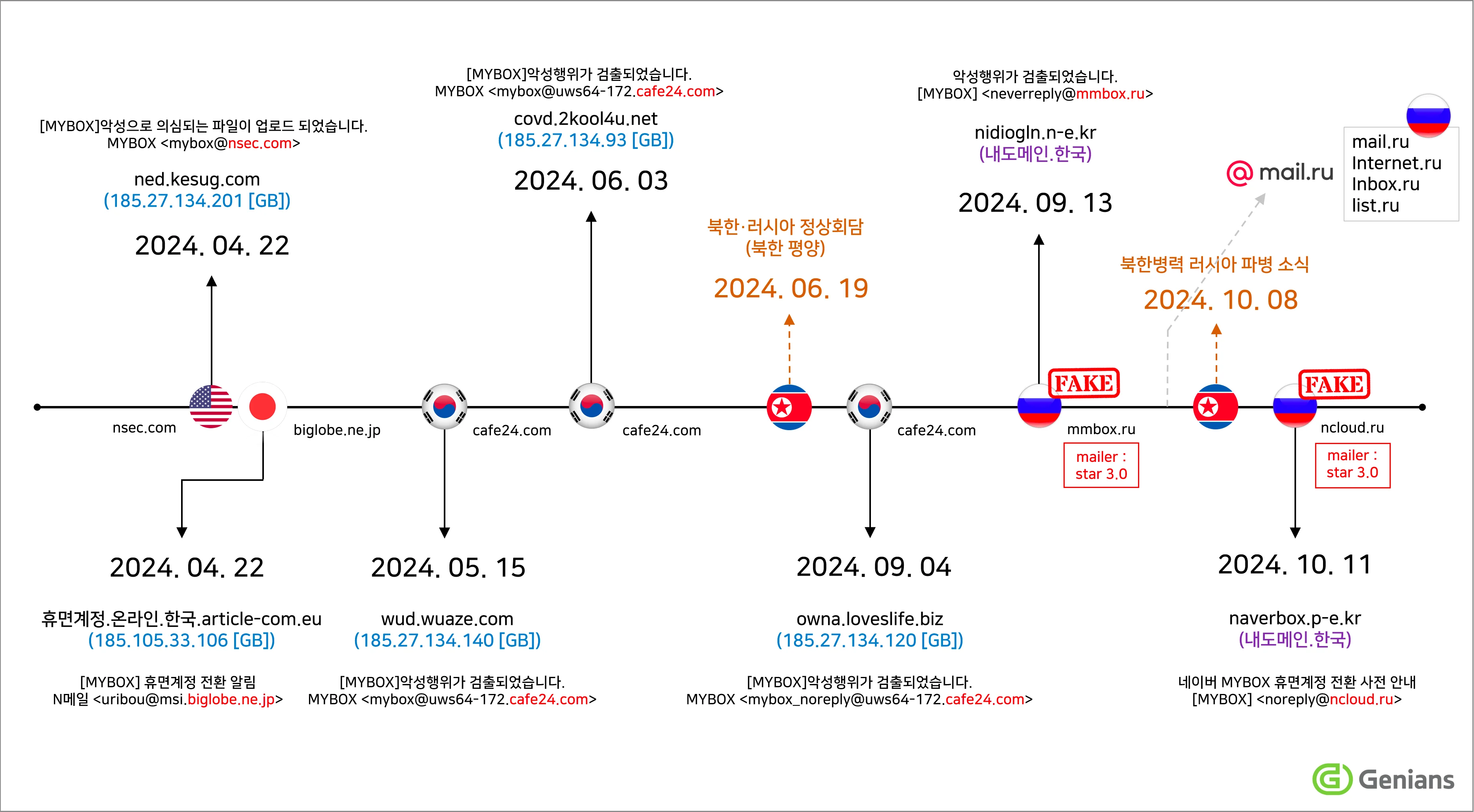

One of the most significant adaptations in Kimsuky’s approach is its transition in email infrastructure. Previously reliant on Japanese services like Biglobe, the group has shifted to Russian domains such as “mmbox[.]ru” and “ncloud[.]ru,” fabricated via the Star 3.0 mailer, previously identified to be used by the threat group in a 2021 Proofpoint report.

Kimsuky threat flow analysis (Source: Genians)

The phishing emails impersonate a wide range of trusted organizations and roles, including government services like the National Secretary, financial institutions, portal company email security managers, and public institutions. These emails are often themed around pressing issues, such as payment deadlines or security notifications, to provoke user interaction.

Moreover, Kimsuky has leveraged ‘MyDomain[.]Korea,’ a free Korean domain registration service, to craft phishing sites designed to mimic legitimate entities. Domains such as “NationalSecretary.Main[.]Korea” and “naverbox.pe[.]kr” have been employed, furthering the group’s ability to deceive targets by mimicking official portals.

The group’s phishing emails strategically lack malware, instead embedding links to credential-stealing websites. This shift not only makes detection more challenging but also aligns with a broader trend of avoiding malicious attachments in favor of URL-based attacks.

Connections to earlier campaigns underscore the evolving threat posed by Kimsuky. The tactics employed, including impersonation and infrastructure changes, reflect a deliberate effort to enhance the effectiveness of their campaigns while avoiding detection.

Here are some key Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) related to Kimsuky’s malwareless phishing attacks:

Phishing Domains and C2 Servers:

- cookiemanager.ne[.]kr

- nidiogln.ne[.]kr

- naverbox.pe[.]kr

- evangelia[.]edu

- wud.wuaze[.]com

- ned.kesug[.]com

- covd.2kool4u[.]net

- owna.loveslife[.]biz

- online.korea.article-com[.]eu

Phishing Email Themes and Senders:

- Sender domains: inbox[.]ru, mail[.]ru, internet[.]ru, list[.]ru

- Phrases like “Payment deadline,” “Payment due date,” “National Tax Service,” and “Blog post restriction information”.

For more information and the full list of IOCs, see the research blog here.

Conclusion

Kimsuky, a North Korean cyber-espionage group, has been a persistent and evolving threat since it was first observed in 2013. With a focus on intelligence gathering, Kimsuky has targeted the government institutions, think tanks, academic institutions, and critical infrastructure primarily in South Korea but also in the United States and Europe.

Kimsuky’s tactics are sophisticated and varied, ranging from spearphishing emails and exploiting software vulnerabilities to using malicious Chrome extensions and custom malware. The group’s ability to adapt and evolve its tactics makes it particularly dangerous.

Furthermore, Kimsuky is not operating in isolation. It is part of a larger network of North Korean APT groups, including the Lazarus Group and APT37. These groups, while operating independently, share similarities in tactics and targets, suggesting a coordinated effort by the North Korean government.

The global reach and evolving nature of Kimsuky’s operations highlight the importance of vigilance and robust cybersecurity measures. As Kimsuky continues to adapt and evolve, so too must the defenses against them.

Security Recommendations Against Kimsuky

Educate and Train Staff: Regularly train staff to recognize phishing emails and malicious attachments. Educating users on the risks of spearphishing emails is crucial.

Keep Software Updated: Regularly update all software to ensure that known vulnerabilities are patched. This reduces the avenues through which Kimsuky can gain unauthorized access.

Implement Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA): Use MFA wherever possible, especially for critical systems and data. This adds an additional layer of security, even if passwords are compromised.

Monitor for Suspicious Activity: Regularly monitor networks and systems for unusual activity that could indicate a breach.

Use Security Software: Employ robust security software that can detect and block malware and other malicious activity.

Collaborate and Share Information: Work with other organizations and government agencies to share information on threats and best practices for defense.

Develop an Incident Response Plan: Have a plan in place for responding to security incidents. Knowing how to respond in the event of a breach is critical.

By taking these steps, organizations can reduce their risk of falling victim to Kimsuky and other cyberespionage groups.

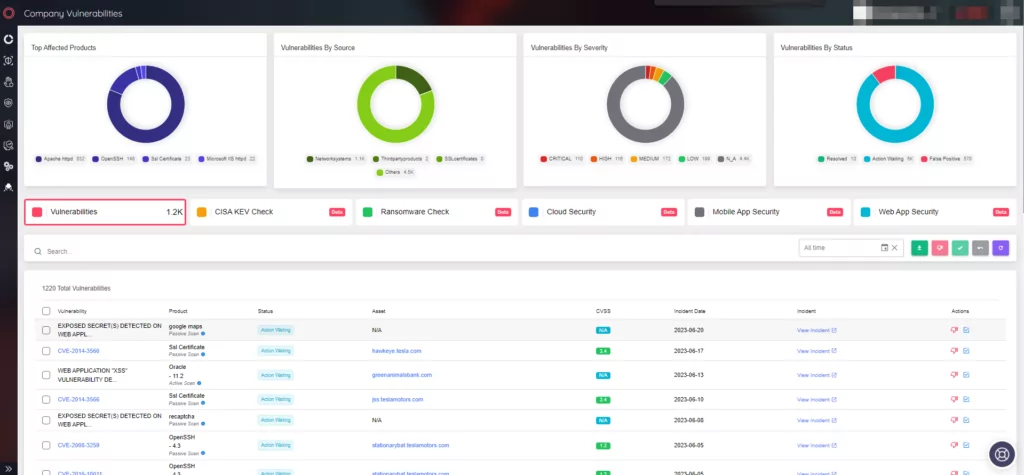

In an ever-evolving threat landscape, staying informed and being prepared are key to being out of danger. Cyber Threat Intelligence is among the best threats to take against a specific group conducting espionage activities. For example, obtaining information about the existing weaknesses in the assets owned by the company will enable the company to take early action against possible threats.

MITRE ATT&CK TTPs Used by Kimsuky

| Technique | ID |

| Reconnaissance | |

| Gather Victim Identity Information: Email Addresses | T1589.002 |

| Gather Victim Identity Information: Employee Names | T1589.003 |

| Gather Victim Org Information | T1591 |

| Phishing for Information: Spearphishing Link | T1598.003 |

| Search Open Websites/Domains: Social Media | T1593.001 |

| Search Open Websites/Domains: Search Engines | T1593.002 |

| Search Victim-Owned Websites | T1594 |

| Resource Development | |

| Acquire Infrastructure: Domains | T1583.001 |

| Acquire Infrastructure: Server | T1583.004 |

| Acquire Infrastructure: Web Services | T1583.006 |

| Compromise Accounts: Email Accounts | T1586.002 |

| Compromise Infrastructure: Domains | T1584.001 |

| Develop Capabilities: Malware | T1587.001 |

| Establish Accounts: Social Media Accounts | T1585.001 |

| Establish Accounts: Email Accounts | T1585.002 |

| Obtain Capabilities: Tool | T1588.002 |

| Obtain Capabilities: Exploits | T1588.005 |

| Stage Capabilities: Upload Malware | T1608.001 |

| Initial Access | |

| Exploit Public-Facing Application | T1190 |

| Phishing: Spearphishing Attachment | T1566.001 |

| Phishing: Spearphishing Link | T1566.002 |

| Execution | |

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell | T1059.001 |

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: Windows Command Shell | T1059.003 |

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: Visual Basic | T1059.005 |

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: Python | T1059.006 |

| Command and Scripting Interpreter: JavaScript | T1059.007 |

| User Execution: Malicious Link | T1204.001 |

| User Execution: Malicious File | T1204.002 |

| Persistence | |

| Account Manipulation | T1098 |

| Boot or Logon Autostart Execution: Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder | T1547.001 |

| Browser Extensions | T1176 |

| Create Account: Local Account | T1136.001 |

| Create or Modify System Process: Windows Service | T1543.003 |

| External Remote Services | T1133 |

| Scheduled Task/Job: Scheduled Task | T1053.005 |

| Server Software Component: Web Shell | T1505.003 |

| Software Discovery: Security Software Discovery | T1518.001 |

| Privilege Escalation | |

| Event Triggered Execution: Change Default File Association | T1546.001 |

| Obfuscated Files or Information: Software Packing | T1027.002 |

| Defense Evasion | |

| Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information | T1140 |

| Hide Artifacts: Hidden Users | T1564.002 |

| Hide Artifacts: Hidden Window | T1564.003 |

| Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify Tools | T1562.001 |

| Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify System Firewall | T1562.004 |

| Indicator Removal: File Deletion | T1070.004 |

| Indicator Removal: Timestomp | T1070.006 |

| Masquerading | T1036 |

| Masquerading: Masquerade Task or Service | T1036.004 |

| Masquerading: Match Legitimate Name or Location | T1036.005 |

| Modify Registry | T1112 |

| Obfuscated Files or Information | T1027 |

| Obfuscated Files or Information: Software Packing | T1027.002 |

| Process Injection | T1055 |

| Process Injection: Process Hollowing | T1055.012 |

| Subvert Trust Controls: Code Signing | T1553.002 |

| System Binary Proxy Execution: Mshta | T1218.005 |

| System Binary Proxy Execution: Regsvr32 | T1218.010 |

| System Binary Proxy Execution: Rundll32 | T1218.011 |

| Use Alternate Authentication Material: Pass the Hash | T1550.002 |

| Valid Accounts: Local Accounts | T1078.003 |

| Credential Access | |

| Adversary-in-the-Middle | T1557 |

| Credentials from Password Stores: Credentials from Web Browsers | T1555.003 |

| Multi-Factor Authentication Interception | T1111 |

| OS Credential Dumping: LSASS Memory | T1003.001 |

| Unsecured Credentials: Credentials In Files | T1552.001 |

| Discovery | |

| File and Directory Discovery | T1083 |

| Network Sniffing | T1040 |

| Process Discovery | T1057 |

| Query Registry | T1012 |

| System Information Discovery | T1082 |

| System Network Configuration Discovery | T1016 |

| System Service Discovery | T1007 |

| Lateral Movement | |

| Internal Spearphishing | T1534 |

| Remote Services: Remote Desktop Protocol | T1021.001 |

| Collection | |

| Archive Collected Data: Archive via Utility | T1560.001 |

| Archive Collected Data: Archive via Custom Method | T1560.003 |

| Data from Local System | T1005 |

| Data Staged: Local Data Staging | T1074.001 |

| Email Collection: Remote Email Collection | T1114.002 |

| Email Collection: Email Forwarding Rule | T1114.003 |

| Input Capture: Keylogging | T1056.001 |

| Command and Control | |

| Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols | T1071.001 |

| Application Layer Protocol: File Transfer Protocols | T1071.002 |

| Application Layer Protocol: Mail Protocols | T1071.003 |

| Ingress Tool Transfer | T1105 |

| Remote Access Software | T1219 |

| Web Service: Bidirectional Communication | T1102.002 |

| Exfiltration | |

| Exfiltration Over C2 Channel | T1041 |

| Exfiltration Over Web Service: Exfiltration to Cloud Storage | T1567.002 |