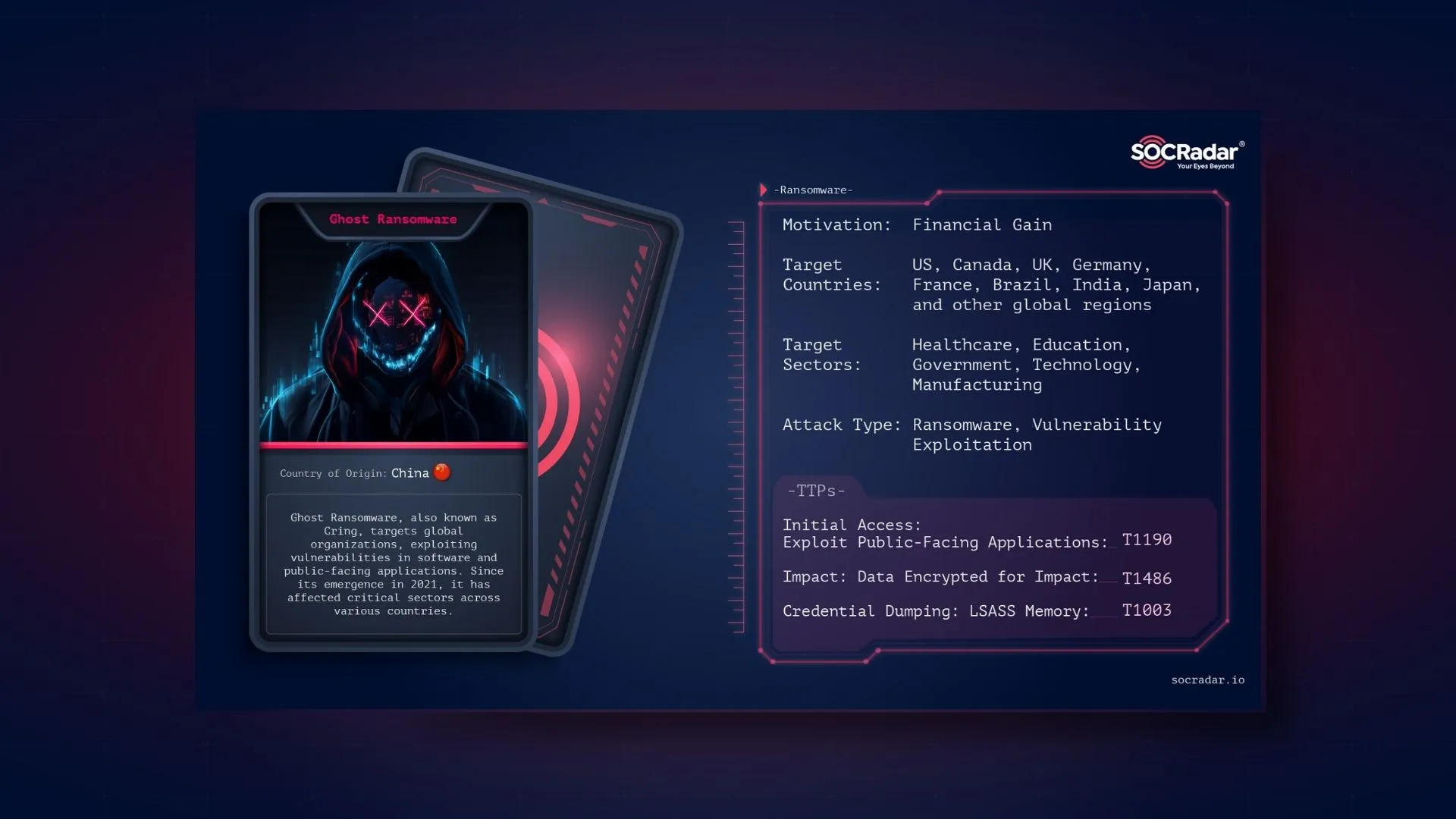

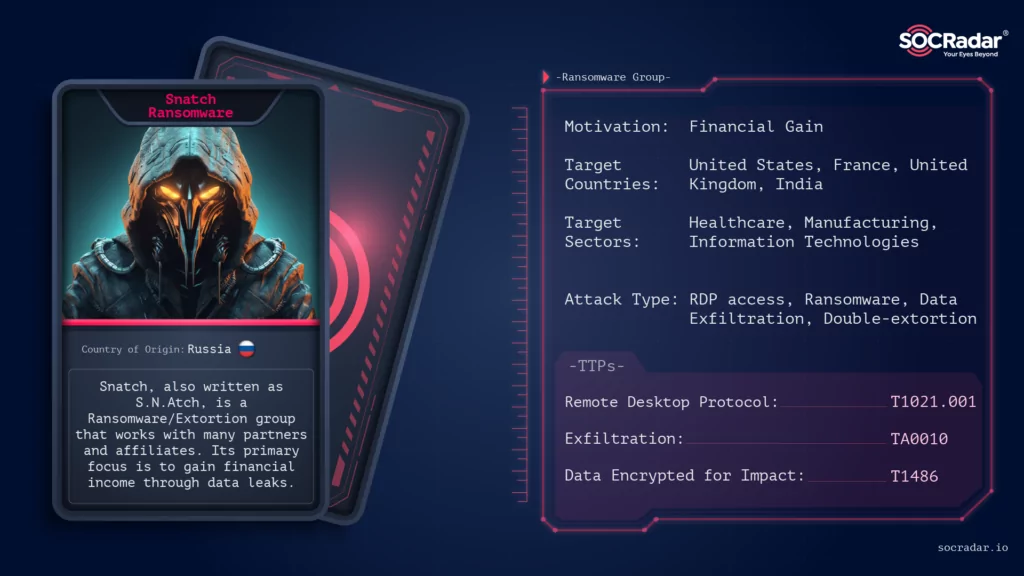

Dark Web Profile: Snatch Ransomware

According to CISA, since the latter part of 2021, the perpetrators behind Snatch Ransomware have persistently adapted their strategies, capitalizing on prevailing tendencies and the operational successes of other ransomware variants within the cybercrime arena.

The threat actors of Snatch have cast a wide net, targeting numerous sectors critical to infrastructure, including but not limited to the Defense Industrial Base, Food and Agriculture, and Information Technology sectors.

The modus operandi of Snatch encompasses ransomware operations that involve the exfiltration of data and double extortion tactics. Following the data exfiltration, which often includes direct ransom demands communicated to the victims, the Snatch threat actors may employ a double extortion strategy. In such instances, if the ransom remains unpaid, the victim’s data is threatened to be published on Snatch’s extortion blog.

Who is Snatch Ransomware?

Snatch Ransomware emerged on the cyber threat landscape in 2019 (?) and has since established itself as a formidable player in the ransomware arena. Initially, the collective was known as Team Truniger, a name derived from the alias of a pivotal member of the group, Truniger, who had formerly functioned as an affiliate of GandCrab. Originating with a distinct modus operandi, the group has been linked to a series of high-profile cyber-attacks, with a significant number of their operations traced back to Russian origins.

The report from the FBI/CISA indicates that Truniger had past affiliations as an operative with GandCrab, a precursor in the Ransomware-as-a-Service domain, which ceased operations after a few years, purporting to have extracted over $2 billion from its victims. GandCrab disbanded in July 2019 and is speculated to have evolved into “REvil,” recognized as one of the most merciless and predatory Russian ransomware groups in history.

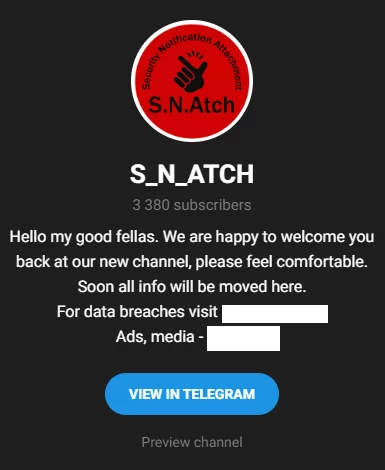

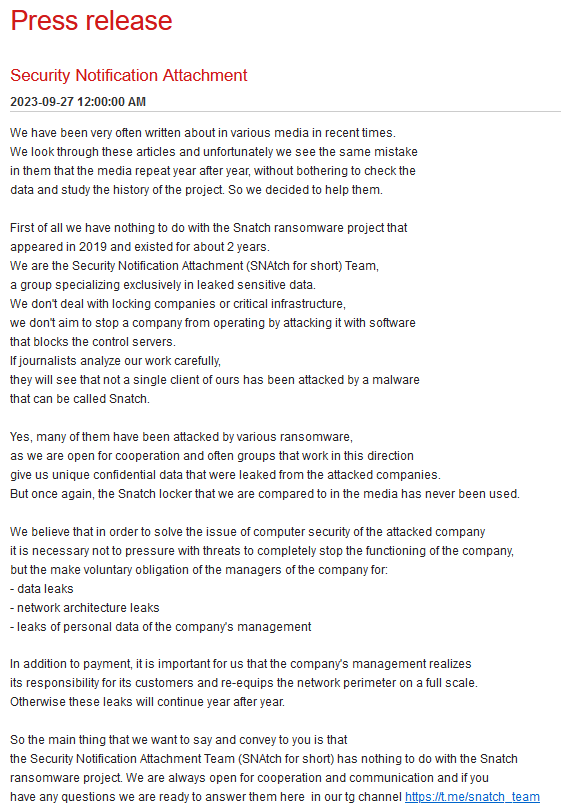

Their name, which seems to be a reference to the movie Snatch, is also written as S.N.Atch (Security Notification Attachment) in the logo of their official Telegram channel. However, here is the twist, contrary to the assertions of security researchers, the operators of Snatch Ransomware present a different claim about their origins and operations.

The threat actors have asserted on leak sites that the allegations from CISA and the security community are unfounded, stating they have no connections to prior Snatch operations and do not adhere to a conventional ransomware model. The group emphasizes its concentration on data leaks and clarifies that the malware utilized in its operations is indirectly sourced from various affiliates and threat actors with whom they collaborate. Additionally, they specify that there is no malware referred to as “Snatch” in their operations.

However, it is not easy to accept their defense as valid. Utilizing domains once used by the Snatch ransomware group has not justified their domain name choices and claims ignorance of the ransomware group’s existence at their inception two years ago. Their website serves as a data marketplace, advocating free access to information and welcoming any team to contribute data for publication. While they deny owning ransomware, they are open to data placement and monetization collaborations.

How does the Snatch Ransomware attack?

Snatch threat actors and their affiliates proactively participate in data exfiltration, utilizing a dual extortion strategy that involves leaking victims’ data if the ransom demands are unmet. Interestingly, these actors have been identified as obtaining previously compromised data from other ransomware variants, intending to coerce victims into paying a ransom to avoid disclosing their data on Snatch’s extortion blog. It also features data related to victims from other ransomware groups, namely Nokoyawa and Conti, further complicating the cyber threat landscape. In other words, if they have the data of companies whose ransom payment has not been received, they do not let go of it for a long time.

Snatch group may not solely manage these attacks themselves, but even if they do not have “ransomware” of their own, there are certain patterns in the attack scheme used by the Snatch team or its affiliates.

According to CISA’s advisory, the threat actors behind Snatch have been known to exploit weaknesses in Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) as a primary method of gaining unauthorized access to victims’ networks. This is often achieved through brute-forcing, where they leverage administrator credentials, sometimes even seeking compromised credentials from criminal forums and marketplaces.

Once inside, the Snatch threat actors ensure persistence on a victim’s network by compromising an administrator account and establishing connections over port 443 to a Command and Control (C2) server, typically located on a Russian bulletproof hosting service. Although blocking such hosting, which you can find the necessary IoCs in the CISA advisory, can directly cut off the connection with CC, in many cases, they can avoid this because intermediary servers and proxies are used.

This meticulous approach to maintaining a foothold within the network underscores the group’s strategic planning and execution. The threat actors have been observed using various tactics to discover data, move laterally, and search for data to exfiltrate. Notably, they utilize “sc[.]exe” to manipulate system services using the Windows Command line and also employ tools like Metasploit and Cobalt Strike for their operations.

In a particular incident, Snatch threat actors have been observed spending up to three months on a victim’s system before deploying the ransomware. During this time, they exploit the victim’s network, moving laterally across it with RDP and searching for files and folders for data exfiltration, followed by file encryption. This extended presence on the network before making a move indicates a calculated approach, ensuring they maximize the impact of their eventual attack.

In the early stages of ransomware deployment, Snatch threat actors attempt to disable antivirus software and run an executable, often named “safe[.]exe” or a variation thereof. In some instances, the ransomware executable’s name consisted of a string of hexadecimal characters, which match the SHA-256 hash of the file, a tactic employed to defeat rule-based detection.

The Snatch ransomware payload then queries and modifies registry keys, uses various native Windows tools to enumerate the system, finds processes, and creates benign processes to execute Windows batch (.bat) files. Sometimes, the program attempts to remove all the volume shadow copies from a system.

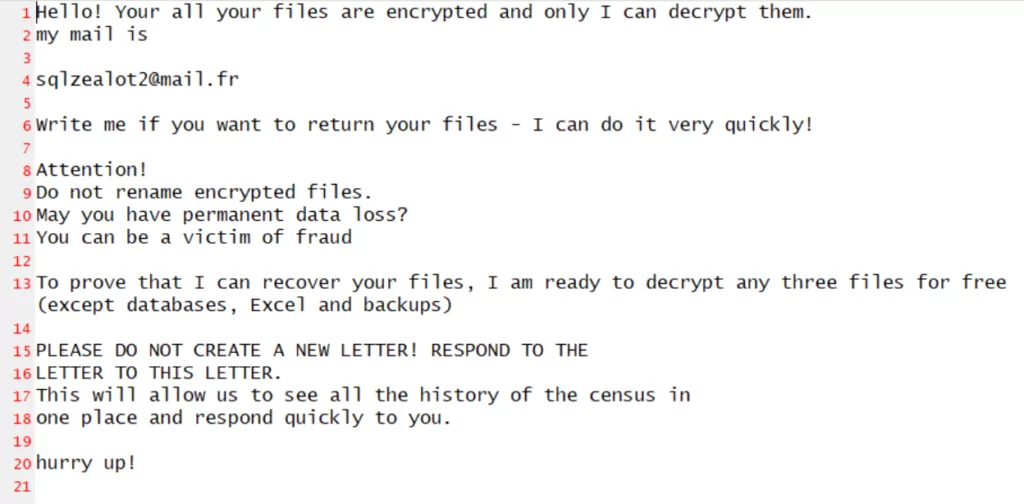

Upon successful encryption, the Snatch ransomware executable appends a series of hexadecimal characters to each file and folder name it encrypts, leaving behind a text file titled “HOW TO RESTORE YOUR FILES.TXT” in each folder. Communication with victims may be established through e-mail and the Tox communication platform, based on identifiers left in ransom notes or through their extortion blog by getting a UUID (Universal Unique Identifier).

Snatch victims may have had a different ransomware variant deployed on their systems but received a ransom note from Snatch threat actors, resulting in the victims’ data being posted on the ransomware blog involving the different ransomware variants and on the Snatch threat actors’ extortion blog.

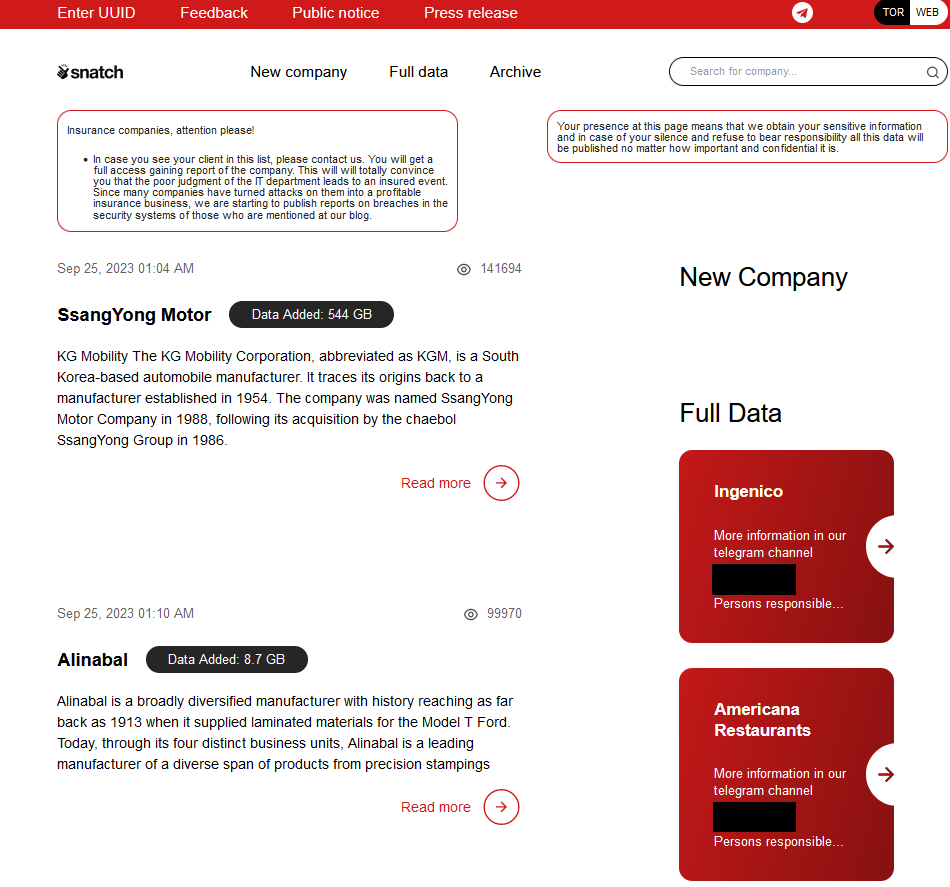

A quick look at Snatch Ransomware’s TOR site

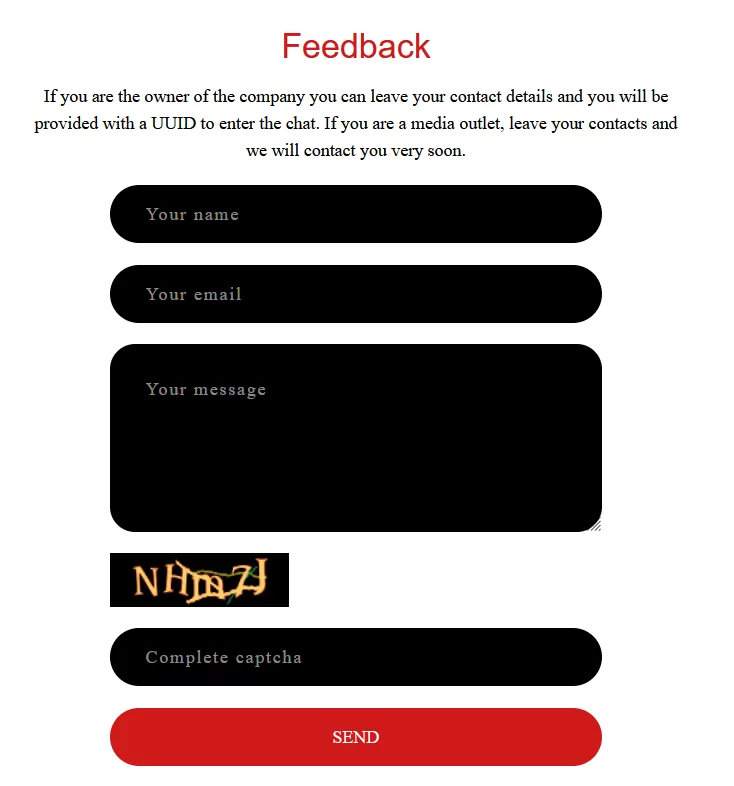

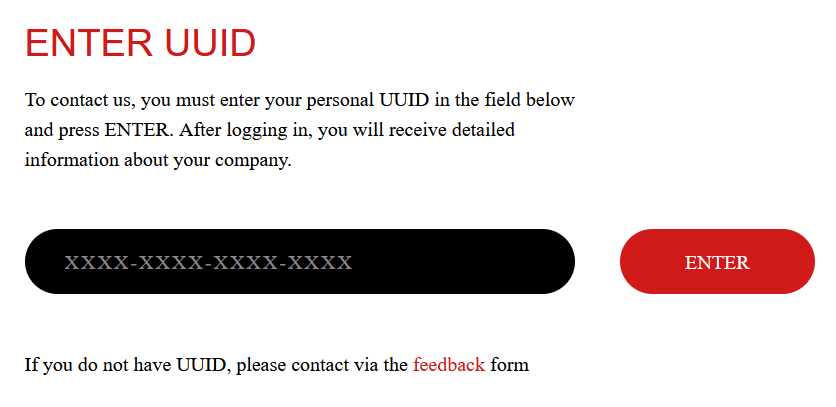

We added a screenshot with a general view of their website at the beginning of the article, but there are a few more noteworthy points. One of the interesting points on Snatch’s leak website is that it includes a “Feedback” section to obtain UUID (Universal Unique Identifier). In this section designed for victims to get identifiers, they are asked to enter their contact information as the company owner.

Once the UUID is received, the next stage can be entered by entering the identifier to view the details about the leak and proceed to the negotiation part.

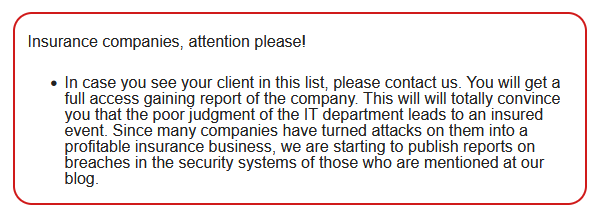

There is an announcement to insurance companies right at the entrance of their website. If there are affected customers, they ask them to contact them and claim that they have given them access to a report about the leak, and they provoke against their customers with a close stance towards insurance companies.

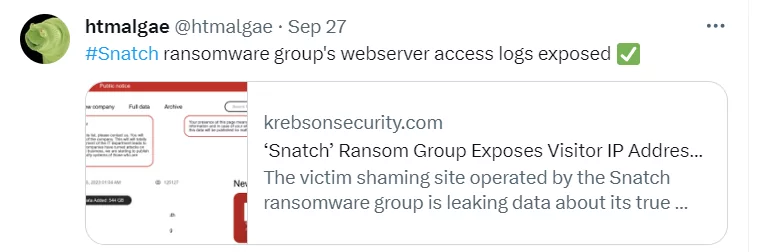

Security researcher htmalgae, whom we interviewed recently, revealed another point on Snatch’s website.

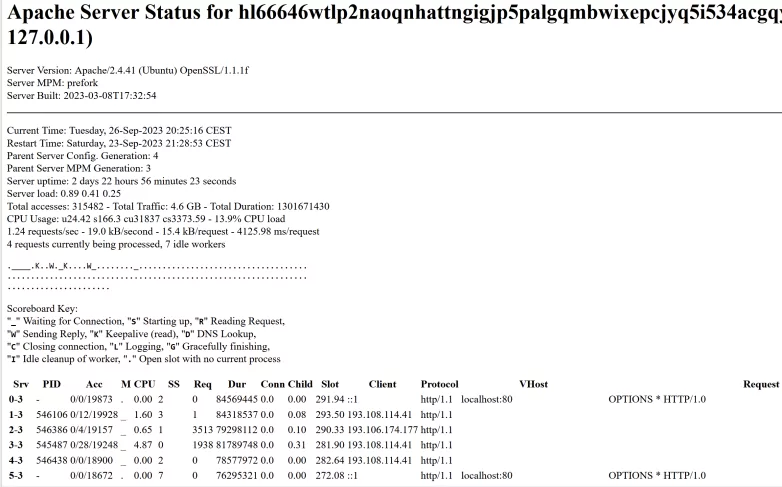

According to research published on KrebsOnSecurity. Snatch, who found themselves inadvertently leaking users’ data of the visitors. The exposed server-status reveals the IP addresses of visitors but also provides insights into the group’s operations and online location. This information is particularly crucial as it gives a glimpse into the group’s internal workings and potentially offers a pathway for cybersecurity experts to explore countermeasures against them.

Digging deeper into the exposed data, frequent visits from specific Russian IP addresses were noted, which currently host or have recently hosted Snatch’s clear web domain names. Furthermore, a connection was discovered to a Russian name, Mihail Kolesnikov, associated with numerous phishing domains tied to malicious Google ads and the Snatch ransomware group. These domains, often mimicking legitimate software companies, have been used to disseminate various malware, including the Rilide information stealer trojan, and have been linked to malicious advertising campaigns on Google.

What are the targets of Snatch Ransomware?

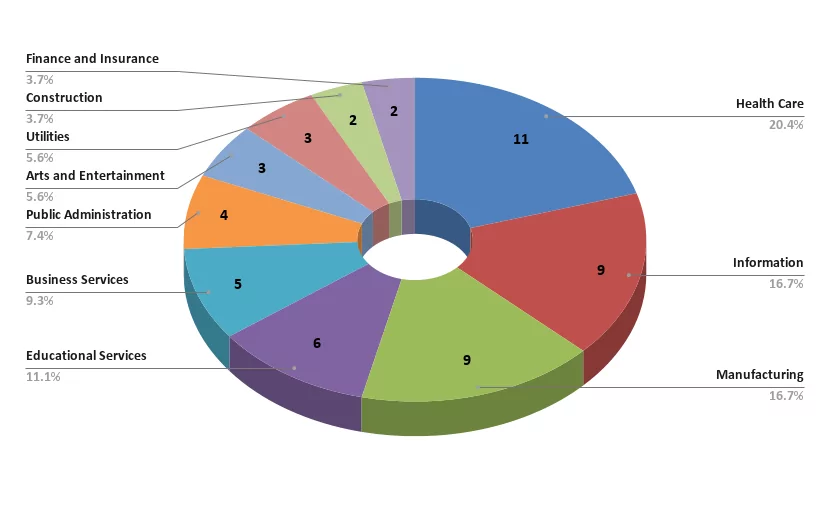

Snatch’s targets include Information and Manufacturing industries, in line with a standard ransomware operator, but one of the notable industries seems to be Healthcare. Although their most significant leaks are government-related, they also frequently target other sectors to meet their financial targets.

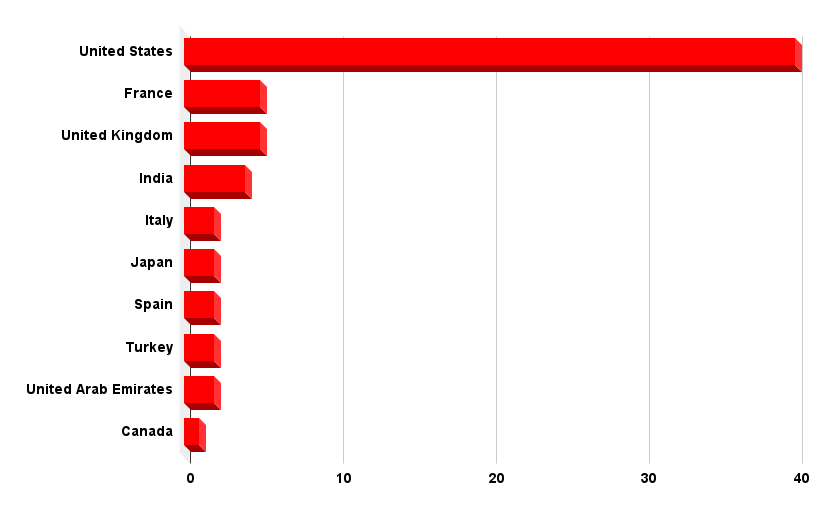

Analyzing the geographical distribution of the organizations impacted by Snatch, one can deduce that their primary operations are concentrated in North America and Europe, with the United States being notably the most heavily impacted country.

Latest activities of Snatch Ransomware

The last victims of Snatch operators, who have not shared any victims since September 25, were South Korea-based SsangYong Motor and US-based Alinabal. Even though they have not published any victims for a week, the attacks are expected to ramp up, considering CISA’s warning.

The victim listed by Snatch on September 19 was the Florida Department of Veterans’ Affairs. Although the group has attracted the attention of the authorities for a long time, this attack also seems to have touched more sensitive points.

Maybe this constituted one of the most significant breaches. On August 21, 2023, data from the South African Department of Defence (DARPA) was exposed by the Snatch ransomware on their extortion platform. The leaked information amounted to 1.6 terabytes and purportedly included military agreements, internal identifiers, and personal details.

The Snatch Ransomware is Getting Grumpy

The Snatch group recently shared a post and revealed that perhaps they are afraid of some developments in the field of cyber security. The Telegram post comes against a significant operation by law enforcement agencies from seven countries, coordinated by Europol and Eurojust. This operation successfully targeted a separate ransomware group responsible for devastating attacks across 71 countries and causing losses in the hundreds of millions. These attacks, involving ransomware like LockerGoga and MegaCortex, led to the arrest of key figures of the group in Ukraine, disrupting their operations.

However, in a bold message, the Snatch group’s recent Telegram post conveys a clear message: they are undeterred by these law enforcement actions. The post reads, “My good fellas, our dear customers! You are deeply mistaken if you think you will be given something for free or your information will not be published.” This statement reaffirms their commitment to their extortion practices and serves as a reminder of their capabilities and intent to continue their operations.

Although their names are not mentioned in Europol’s operation, the reason for making this statement seems to be that they use other groups’ ransom and exfiltration attacks for their interests and extort through leaked data.

The Snatch group emphasizes that even if they cease procedures for any reason, all information in their database will be automatically released, affecting all listed companies. This could involve publication on their website or specialized forums on the web or Tor, posing a persistent threat to numerous entities.

Conclusion

Despite numerous indicators suggesting otherwise, their denial of affiliations with the 2019 Snatch Ransomware is intriguing. This denial appears to stem from their intention to forge a new paradigm, potentially establishing a RaaS group as an overarching entity or a foundation for all extortion. So, although it has not been named yet, it seems that it will appear as a different concept in the future. Because of the complexity of this situation, it is not feasible to attribute a particular malware or ransomware to the group or maybe even categorize it as a ransomware group.

In closing, the activities and strategies of Snatch underscore the urgent need for robust, coordinated, and proactive cybersecurity defenses among organizations and nations alike. The evolving threat landscape, marked by the persistent and innovative tactics of groups like Snatch, demands a vigilant and adaptive system to cybersecurity, ensuring that defenses evolve in parallel with emerging threats and that insights from analyzing Snatch’s operations act as a catalyst for enhancing cybersecurity frameworks and collaborations.

Security recommendations against Snatch Ransomware

- Maintain Offline Backups: Ensure that you have offline backups of your critical data to prevent disruptions and data loss.

- Implement MFA: Enable and enforce phishing-resistant multi factor authentication MFA to add an additional layer of security.

- Monitor RDP Usage: Conduct network audits to identify systems using RDP, close unused RDP ports, log RDP login attempts, and implement account lockouts after a certain number of failed attempts.

- Educate Employees: Ensure that your team is aware of the risks of phishing emails and knows how to identify and report them.

- Update and Patch Systems: Regularly update and patch systems to protect against known vulnerabilities that could be exploited by ransomware.

- Network Segmentation: Implement network segmentation to limit lateral movement within the network in case of a breach.

- Implement a Security Framework: Adopt a security framework that aligns with your organization’s needs and ensures that all aspects of your cybersecurity posture are addressed.

- Incident Response Plan: Develop and regularly update an incident response plan to ensure that your organization can respond effectively to a ransomware attack.

MITRE ATT&CK TTPs of Snatch Ransomware

| Tactic | Technique ID | Technique Title |

| Reconnaissance | T1590 | Gather Victim Network Information |

| Resource Development | T1583.003 | Acquire Infrastructure: Virtual Private Server |

| Initial Access | T1078 | Valid Accounts |

| T1133 | External Remote Services | |

| Execution | T1059.003 | Command and Scripting Interpreter: Windows Command Shell |

| T1569.002 | System Services: Service Execution | |

| Persistence | T1078.002 | Valid Accounts: Domain Accounts |

| Defense Evasion | T1036 | Masquerading |

| T1070.004 | Indicator Removal: File Deletion | |

| T1112 | Modify Registry | |

| T1562.001 | Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify Tools | |

| T1562.009 | Impair Defenses: Safe Mode Boot | |

| Credential Access | T1110.001 | Brute Force: Password Guessing |

| Discovery | T1012 | Query Registry |

| T1057 | Process Discovery | |

| Lateral Movement | T1021.001 | Remote Services: Remote Desktop Protocol |

| Collection | T1005 | Data from Local System |

| Command and Control | T1071.001 | Application Layer Protocols: Web Protocols |

| Exfiltration | TA0010 | Exfiltration |

| Impact | T1486 | Data Encrypted for Impact |

| T1490 | Inhibit System Recovery |

Further details, recommendations, and an extensive list of the Indicators of Compromise (IoCs), are available on the official advisory on CISA.

Indicators of Compromise for Snatch Ransomware

Below are the Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) obtained from the SOCRadar XTI Platform, which could be added upon the IoCs by CISA.

| Indicator Type | Indicator |

| IP | 80[.]66[.]64[.]15 |

| IP | 194[.]168[.]175[.]226 |

| IP | 193[.]108[.]114[.]41 |

| HOSTNAME | www-docker[.]top |

| HOSTNAME | www-discord[.]com |

| HOSTNAME | www-citrix[.]top |

| HOSTNAME | www-basecamp[.]top |

| HOSTNAME | sntech2ch[.]top |

| HOSTNAME | snatchteam[.]top |

| HOSTNAME | sn76930193ch[.]top |

| HOSTNAME | www.real-vnc[.]top |

| HOSTNAME | mlcrosofteams-us[.]top |

| HOSTNAME | libreoff1ce[.]com |

| HOSTNAME | ibreoffice[.]top |

| HOSTNAME | dwhyj2[.]top |

| HOSTNAME | ccleaner-cdn[.]top |

| HOSTNAME | adobeusa[.]top |

| HOSTNAME | pittsburghcitygirls[.]com |

| HOSTNAME | www-microsofteams[.]top |

| HOSTNAME | www-fortinet[.]top |